The sign language glove is an idea whose time has come! Or has it?

Could this tech tool be helpful for Deaf people? Or it is just so much hand-waving? Not everyone in the world of singed language is wild about this invention. But why not?

We’ll find out on this episode of Talk the Talk.

Listen to this episode

You can listen to all the episodes of Talk the Talk by pasting this URL into your podlistener.

http://danielmidgley.com/talkthetalk/talk_classic.xmlVideo interview with Adam Schembri

This video has captions. Turn them on with the CC button.

Daniel chats with with Adam Schembri, expert on signed languages, on the feasibility of a sign language glove, how to make things better for Deaf people, and how he got into signed languages.

Transcript

DANIEL: A lot of people I think feel like sign languages are just one thing where they say “Oh, I’m going to learn sign language.” But one of the things I’ve noticed when I’ve delved into this is that sign languages are really varied. There’s a lot of variation there. Can you tell me a little bit about how they’re different from each other?

ADAM: The main area of difference is really, as far as we can tell, in vocabulary, but there are grammatical differences. But I suspect — it’s still a working hypothesis — most of us work on the hypothesis that signed languages are more similar to each other grammatically than unrelated spoken languages. But there is a lot of cross-linguistic difference, that’s for sure. What’s amazing is that signs can be iconic in different sign languages, but of course they can choose different features in the form of the sign. So one sign in Auslan for “cat” is a sign that looks like this <sign> okay, it’s just a simple sign that refers to patting.

DANIEL: Mhm.

ADAM: The sign used in British Sign Language for “cat” is like this: <sign> it looks like the whiskers of a cat. But my favourite is a sign used in Japan, in Japanese Sign Language for “cat” which is like the licking the paws, the cat licking its paws, so like that. So they each pick different aspects, distinctive aspects of the cat’s appearance or its behaviour. So you get a lot of — even those signs that are often iconic, there’s some link between the form and the meaning of the sign. This can vary enormously across different sign languages. There’s lots of great examples in Japanese sign Language. So for example, the sign for “me” or “I” in Japanese Sign Language involves a point at the nose, okay? Whereas in Auslan and BSL, it’s at the chest. The sign for “siblings” in Japanese Sign Language is interesting! <sign> It looks like flipping the bird!

DANIEL: With both hands!

ADAM: It looks like — you know, yeah. So you extend the middle finger from the fist and you wave your hand around in the air kind of thing. So that means “sibling”. But for, you know, for “older sibling” then you move one of those hand shapes up compared to the other one…

DANIEL: Right.

ADAM: For “younger sibling” you move it down. So I mean, there’s a lot of — yeah, there is a lot of variation. I’ve run a bit of a campaign on Twitter whenever I spot organisations referring to “sign language” in the singular, I kind of respond with the hashtag #signlanguages

DANIEL: Very good!

ADAM: Because even people in the Deafness area forget, and they talk about sign language interpreters and you know, sign language classes and they forget and they should be more specific. So often when they try to engage with their audience to attract people to a class, for example, they’ll say “Come and learn sign language,” but once you get there, then you find out — oh actually it’s just Auslan or it’s just BSL or it’s just American Sign Language. It’s not like — there’s no universal sign language.

DANIEL: Now that I’m thinking about it, I’m also thinking: Gee, you know, in my spoken English I swap between different styles and different registers, you know: highfalutin and casual throughout a day. Does that exist in, say, Auslan as well?

ADAM: Yeah, I mean the registers — there are there are definitely different degrees of formality. There are signs that are a bit slangy that you wouldn’t use in a more formal context, for example. There are ways of signing that are more formal, so obviously relating to the clarity of the production of the message. So we did a study in Auslan looking at the fact that signs — that in citation form — so in their dictionary form — are made on the forehead — so a sign like “know,” where you tap the side of your forehead with your extended thumb from your fist, so that means “to know something or someone”. That sign in a formal context will be produced there, but often in conversation the sign will be lowered so that it’s produced in the middle of the signing space just in front of the signers chest, because that’s where of course your hands are most easily held. So it’s kind of economy of effort. So you just move your hands directly in front of the body and so in an informal context that will often occur. The sign will drop and there are signs like “know” that do that quite a lot, and as well as that the sign for “I” or “me” which involves an index finger pointing at your chest, it can assimilate. It can take on features of a sign that follows it, so often if you want to sign “I do not know”, you know in a formal context, you extend the index finger very clearly from the fist and point it into your chest, and then you have a flat hand which you hold near your forehead and you move away, okay, as you shake your head and that’s “I don’t know” but often what you get in an informal context is the sign for “me” is the same handshape. It’s just a flat hand held at the middle of the chest, and then you just get a movement away. And that’s literally Auslan for “Dunno.” <Laughter>

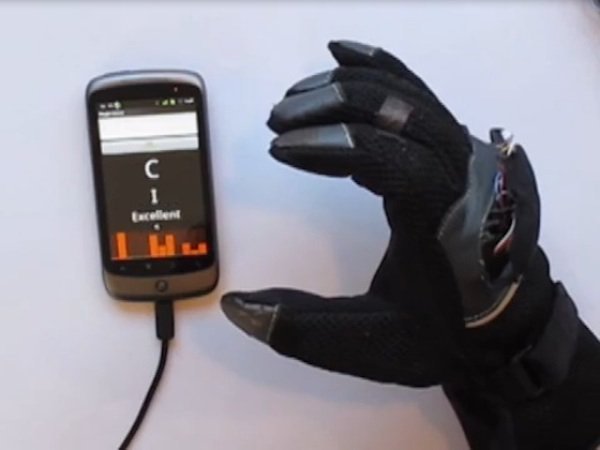

DANIEL: All right, well, already I’m seeing a few problems in the concept that I wanted to talk to you about, and that is that I’ve been noticing a few articles this week about people who have invented a sign language glove.

ADAM: Mm-hmmmm…!

DANIEL: We’ve already mentioned a few things that might be snags, right? Because first of all, there’s variation. But that’s okay, I can figure that. But there’s also — I mean, the gloves would cover your hands. But that’s just your hands!

ADAM: Yes, exactly.

DANIEL: We’re talking about where it is on your body, and where it is, like, on your head and where it’s moving.

ADAM: Yeah. I mean, also, as I pointed out, the fact that when you sign “don’t know,” you often shake your head. So this is one of — this is the first major problem with the signing glove technology, is that it seems to be based on the assumption that only the hands are necessary to read the sign language signal. But of course, sign languages use other parts of the body, not just the hands. In some cases, some signs don’t involve the whole arm, so the sign for “Scotland” <signs> — okay — is a movement of your elbow so it’s like the gesture people often use for “chicken”. Okay?

DANIEL: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah!

ADAM: So it’s just a movement… The handshape is less important! You can have a variety of handshapes. What is significant, what is salient — the articulator — is the whole arm moving backwards and forwards next to your body. So there are signs that don’t involve the hands, then there are other features of sign languages like movement of the head, changes in facial expression, mouth gestures…

DANIEL: Wow. Can you give me an example of those?

ADAM: Well, a mouth gesture for example… If you want to sign “I’m driving”, so you hold your hands as if you’re holding a steering wheel in front of you. And if you want to sign “I’m driving in a normal fashion” — okay — you will have a small pout on your mouth. Like that. And that means “driving in a normal fashion.” Okay, if you want to say you were driving after maybe, you know, too many drinks…

DANIEL: Which you should never do!

ADAM: Or if you were driving without paying attention, okay, then you would protrude your tongue and that means “driving carelessly.” So the mouth gesture can have adverbial meanings. It can affect the meaning of the sign. So there are mouth gestures, there are head movements like shaking your head for negation, to negate something, or nodding your head to affirm something, raising your eyebrows for a yes/no question, following your brows for a wh- question. So there’s so much more than just the hands involved! So this is the big hurdle for glove technology is you actually need a body glove! <Laughter>

DANIEL: Okay, all right, well — that makes things a little more complicated, I guess!

ADAM: Secondly, what does the person who’s watching the Deaf person do? So the Deaf person presumably has these gloves, okay? So you can go from a sign language into a spoken language, but then what happens to the hearing person who doesn’t sign?

DANIEL: Mm-hmm.

ADAM: How do they respond?

DANIEL: They would need some kind of device as well!

ADAM: Yeah, exactly! I mean it’s just — you just feel like saying “Just learn to sign!” <Laughter> I mean obviously, actually, you know, Deaf people have all sorts of ways of communicating with people who don’t sign. They’re experts at it. They live their entire lives surrounded by people who don’t use sign languages. So they’re really good at extracting meaning from, you know, seemingly random gestures and mouth patterns from people who don’t sign. They’re very good at it. They get by every day without this kind of technology by coming up with other ways to communicate. Some deaf people when they go into a — you know — if you’re in a restaurant, you can point at the menu, you could write things down, you can use a surprising amount of shared gestural knowledge. There’s so many ways that you can communicate if you choose not to use spoken language in a particular context.

DANIEL: Okay, so I can see why the sign language glove is kind of a terrible idea. But it’s a very popular idea! People seem to keep coming up with this thing again and again. Why is that?

ADAM: I think to be fair on the computer science and engineering community, I think they are fascinated by the problem. Okay, it’s a problem that has application. So it has applications, I think, with human-computer interfaces. So even though it’s often billed as a tool for communicating with Deaf people, actually I think, you know, as we see in the increasing sophistication in which we interact with computers, you know, so the swiping of the phone screen, and the touchscreen, that kind of thing, the writing on an iPad, or all these kinds of interfaces — I think that’s really where the applications are and that’s what’s driving the interest from the electrical engineering and computer science kind of community. They’re interested in developing the technology that can deal with this, and they often I think, you know, bill it as a way to assist communication between Deaf and hearing people. But the fact is, often they don’t work with people from the Deaf community. They create this technology without a lot of — without working with sign language researchers, without working with Deaf community members in many cases. Some people in the industry do work closely with Deaf communities, and with sign language linguists, but not everyone does. So here in the UK, we have computer scientists who are really interested in gesture and sign language recognition technology, so being able to recognise sign languages in a video clip — okay — so that translation could be partly automated…

DANIEL: That would be really good.

ADAM: That’s very useful! That’s very useful. and it’s very… we’re working closely with these kind of computer geeks because that has direct applications in our linguistics research. So if we can get any kind of automation, automatic recognition of sign language data, video data, then that will help with our analysis; for example, our building video collections of data. Because at the moment, we have to manually translate every example of video data that we get. We have to look at the signs, decide what they mean, and then, you know, enter in some kind of translation. If any of that could be automated and speed up the process of sign language coding, that would help researchers like us enormously. It would also help sign language interpreters, it would help sign language teachers, it would have a lot of applications. So that kind of technology we’re all — us sign language researchers are really keen on. And as I said, my colleagues at University College London are cooperating with some computer scientists from Oxford who are some of the leading figures in this kind of research for gesture and sign language recognition.

DANIEL: So I guess the real solution is: work on approaches that look at the whole body, maybe via video. But also, that’s only gonna be half the picture, because as you say, it gets things out but it doesn’t get anything in.

ADAM: Yeah.

DANIEL: Is the solution for everybody just to learn a signed language that’s near them?

ADAM: Well, I recognise now that not everyone will have the opportunity to learn a sign language, but we already have a solution to the problem and they’re called sign language interpreters. <Laughter> And you know I trained as a sign language interpreter myself. I trained as an Auslan English interpreter in Australia back in the 90s, and I did a little bit of work in the industry for a few years. I don’t make a great interpreter because being neutral is not something that comes easily to me! <Laughter>

DANIEL: Just disappearing!

ADAM: Yes! So you know one of the aspects of sign language interpreting which I admire greatly in professional sign language interpreters is their ability to control their facial expressions (except for while they’re signing), so that they’re only conveying the message that’s coming from the speaker or from the signer to the speaker. Some of my first interpreting jobs were for two Deaf friends of mine and colleagues who were studying linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney and so they were like “Great! You’re the guy! You’re doing a PhD in linguistics! We want you to interpret!” But actually of course, you know, I’d be hearing some lecture content that I didn’t exactly agree with sometimes! <Laughter> And so there’d be a little arch of my eyebrow, something that would give me away! And the Deaf person who’s looking at you the whole time to get the message, you know, mostly looking at you, occasionally looking at the lecturer, or the board, or other people in the room, but mostly looking at you — they pick it up!

DANIEL: You couldn’t resist that eye roll, could you, Adam?

ADAM: And they’re like, “What? What? What?” “Adam, you disagree?” I mean that’s the thing: I’ve got these big — I’ve got these gigantic very mobile eyebrows, which I can’t control, and yeah, my Deaf clients would be like “What, you disagree with the lecturer?” And I’m like “No, no! I’ll tell you later! I’ll tell you later! I need to keep interpreting!” But they’d be like, “No, tell us why! Tell us why!” And of course you can have a whole side conversation with the Deaf student, and it wouldn’t disturb the lecturers because it’s silent and you’re in the corner somewhere out of view! It’s a really difficult skill to master, for the fact that, you know, you are a person; you’re not a black box obviously, you are a human being. But you have to you have to keep the focus on the message and not edit it, or keep a running commentary on it! <Laughter>

DANIEL: You know, I keep noticing these stories where people are amazed that a sign language interpreter will be expressive! This just happens over and over again, and I just roll my eyes.

ADAM: I know, I know. I mean, some of the ones that have featured particularly in the American media, you know, they are very expressive examples of American Sign Language users. They are highly expressive, and not everyone is expressive as some of the interpreters and the presenters that you’ve seen in in social media. There is a lot of variation in degrees in those kinds. But what you see is well within the normal range. So yes, the fact that people — that’s part of what sign languages are! That’s part of how they work! Because everything has to be visual, so the equivalent of intonation, stress, you know, emphasis — all these things have to be realized visually. And there’s also other stuff that’s going on that might — so a furrowed brow during a wh- question might be misinterpreted by a non-signer as a sign of anger! So often there’s some… there’s some degree of misinterpretation of some of the, you know… or like the tongue protrusion mouth gesture that I gave you. You know, that might look like some kind of negative comment on something! So there is also… because there are aspects of sign languages and gesture that hearing and Deaf people share, but they’re also aspects that are quite different. And so non-signers might not be aware that certain things that they think — like the raised middle finger, which is common in a number of traditional Auslan signs for example, without any association with the with the obscene gesture — in fact, you know a sign like “holiday” involves the extended middle finger from the fist being moved in circles in front of the signer, and it looks like, you know, it looks like something quite rude or obscene! So you know there’s often misunderstandings like that. When people see interpreters, they think they understand what they’re seeing, but they don’t.

DANIEL: Wow. All right. Now, I know where to get a sign language interpreter, but I know that not everybody does, so that can’t be the way forward for everybody. I’m trying to think of something magical that we can do to help boost representation and turn down the language discrimination that happens for Deaf people.

ADAM: Well, yeah, I mean the number one way to do that is to sign up to an Auslan class in the case of Australia. Sign up to a sign language class, absolutely. Even if you only do, you know, you only complete it to a certain level, then at least if you have some basic sign language skills that you can use when you encounter a Deaf person, you know, that makes a huge difference, just even having a little bit of the basics. Or even understanding that, you know, when you are interacting with a Deaf person, you make eye contact, you look directly into their face, you know, you make sure that your communication is in their line of sight. You don’t kind of, you know, natter away and look — yeah! look into your bag — exactly! — or point at the menu and speak at the same time so that the, you know, their attention is potentially divided, you know. You point, then you speak, then you point again, you know. So you bracket the behavior so that they can see what you’re pointing at. And give an opportunity to read your lips as well, or look at your facial expression, or look at your gestures. So even basic tips like that make a huge difference. I was surprised because the other day we had a guest presenter from Nottingham Trent University which is a university not far from here at the University of Birmingham, and she was talking about having a Deaf student in her class and she was referring to the interpreter as the “signer” and she described the student as someone with “hearing difficulties” and I was really disappointed to hear this because I think that people like lecturers at university who have Deaf students in their class, they really should be briefed by the university’s student support services on the appropriate terminology. So that person sitting next to you, who might have an undergraduate degree or postgraduate qualification in interpreting is not a “signer.” They’re an interpreter, okay? It’s a professional qualification. You can’t do this job without appropriate training, without — in Australia, you know, you get accredited by the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters like everyone else, like all other interpreters and translators do in Australia. So you have to sit an exam, you have to study, you have to be trained to do this. So it’s a profession. So acknowledging that the interpreter is an “interpreter” and you know is a professional is one thing, not calling them a signer. Secondly, knowing that people who use sign language are Deaf people. That’s the term that they use. They say that they are Deaf. There’s no stigma associated with someone from the Deaf community, you know, using the term Deaf. But often hearing people, because of all this political correctness around Deafness and disability and ethnic minorities, and — you know, I hate the term “culturally and linguistically diverse”. Okay? My father’s family was a hundred percent Maltese. How would they be culturally and linguistically diverse? I mean, yes, they were culturally bilingual in English and Maltese. But you know, I hate this term! I guess it was supposed to be introduced to describe — I mean, and how are English-speaking people NOT culturally and linguistically diverse? You’re from the US, right?

DANIEL: Right.

ADAM: Okay, so your culture is different from Australian culture. We are culturally and linguistically diverse, even though we both speak English , we’re from different… I hate this kind of stuff but anyway. All the words that are used around disability, you know, people don’t know what terms “hearing difficulties”, “hearing impairment” — but actually people in the Deaf community are just… they call themselves Deaf people.

DANIEL: Well, those are some great suggestions and that has made me think about stuff that I hadn’t thought about before. Is there anything else that people really need to know about Deaf people?

ADAM: I think that one of the key things that surprises many hearing people — and you might not know that you’re a hearing person because until you interact with Deaf people you never hear this term

DANIEL: You’re right, I am.

ADAM: But we are. You and I are hearing people, okay? So hearing people are surprised that many Deaf people feel neutral about their Deafness or even positive! I think that surprises a lot of hearing people. So for example when a Deaf child is born to Deaf parents, for many Deaf people that is a source of joy!

DANIEL: Because then that means that their culture will continue.

ADAM: Yes, and also because if a Deaf person is born into a Deaf family, we know they have the best opportunities for normal language development because they’ll be exposed to sign language from birth. So this kind of neutral-to-positive feelings about Deafness often comes as a surprise to hearing people, I think, who are not familiar with the community, and who think about deafness as “hearing loss” and as a negative thing. Deaf activists like to promote the idea of “Deaf gain”

DANIEL: Hmm! Not hearing loss

ADAM: Not hearing loss. Deaf gain! So for example, I saw a tweet the other day about this Deaf American guy who wears hearing aids and he has digital hearing aids which are quite powerful, so he can hear quite a lot with the digital hearing aids. But he just videoed himself signing in ASL, “I just arrived in this restaurant, and there’s a screaming baby right next to me.” And he just takes off his hearing aid and he goes, “Deaf gain!”

DANIEL: That’s great! Yeah, and you know I always thought of deafness as a disability, but I think now I’ve realised it’s only really a disability in the context of a culture that doesn’t understand deafness.

ADAM: Yeah. Exactly. And we do have lots of examples of communities around the world in which there are disproportionately high numbers of Deaf people in that community. We have some in northern Australia. There are some communities in the Northern Territory where there are disproportionately high numbers of Deaf people within that particular Indigenous community, and what happens in those communities is that everyone within that community has some degree of sign language skill, okay? And so there are a number of those communities all around the world. There’s another one in northern Bali, there are communities — they’re called Deaf villages, okay, because they’re often small remote communities and we’ve discovered them all over the world. They’re everywhere. There seem to be dozens and dozens of them all around the world. So for example the Bali case, Desa Kolok, this village in northern Bali, there are about two thousand people in the village and about fifty people in that community are Deaf. So every extended family probably has a Deaf member, and how that has happened is because the gene for deafness within that population has been expressed disproportionately more frequently because there’s been lots of intermarriage within that community, which has meant that the deafness gene has become quite dominant in that community. Now what we know is that there have been generations of Deaf people in that community. Everybody signs to a certain — hearing and deaf sign in that community. There are all sorts of cultural practices that are reserved for Deaf people. So for example, for some reason in the village, only Deaf people can bury the dead, only Deaf people can look after the plumbing in the village. There is a special Deaf dance that Deaf people do at certain times to celebrate. They believe, because it’s a Hindu community, they believe there is a Deaf god that brings deaf people into the world.

DANIEL: Wow.

ADAM: And so they are fully integrated into the life of the community. There’s no real Deaf community there, because they are part of that community, in general. So it’s recognised that they are different from hearing people, but they are not treated any differently because everyone signs. So they are fully integrated into that community. So yes, in that community being Deaf is hardly a disability at all. It’s just seen as a normal variant of being human. So we know that part of the problem for Deaf people in a large country like Australia is the fact that there are relatively few of them. And so most people go through life without experiencing extended contact with the Deaf community and so they don’t — their perception of what deafness is is inaccurate. They see it as a kind of isolating, lonely kind of disability, whereas most of the Deaf people I know have very busy and fulfilling social lives! And you know, loneliness is not a problem! It’s a small community, it’s a tightly knit community, and it’s frustrating because it takes a long time to learn to sign fluently, like to learn any other language. I generally found that I was lucky because my first long-term partner — he had Deaf parents, so that’s how I got involved in the community through that connection. But it took me a long time, because he was a native signer and he grew up signing, and he would sign really very rapidly and fluently with his Deaf parents and other Deaf people in his family. He had other Deaf relatives: Deaf aunts, uncles, cousins. I just would look at it in awe and say “Oh my god, I’m never gonna master that,” you know. And he wouldn’t teach me! He was like, “No, I’m not gonna teach you! You go to a class!” Finally, I started going to a class. And the funny thing is, you know, that was a long time ago, but I’m still very much — like, I started learning when I was about 25, and now I’m 52 and what that means is I’ve spent nearly all my adult life having some contact with Deaf communities, and so it’s a big part of my life. I can’t really imagine not being part of this community and this language. It’s enriched my life enormously, and you know, I’m currently dating someone, and you know I’m kind of teaching him a few signs because I can’t imagine, you know, for me the idea, I mean — I would like to have a long-term relationship with someone else who could sign because it’s such a big part of my life that, you know, we’re only been dating six months but I’m already teaching him sign!

DANIEL: He should go to a class! <Laughter>

ADAM: Yeah, he should go to a class! I’m trying to encourage him. Yeah, as I said, my life has been enormously enriched by this experience, and I think the same would be true for anyone, any hearing person who decides to learn a sign language and to work with Deaf people. The other key message is — yes! Australian technological ingenuity was involved in the development of the cochlear implant, okay? Which is an amazing technology. It doesn’t cure deafness, but it does — for a lot of Deaf people, it does increase their access to spoken language. So you know, from many many Deaf people it’s a very positive thing. But one thing that concerns me is that many of the organisations that promote the cochlear implant to hearing parents of Deaf children don’t talk about the possibility of bilingualism, okay? Often the cochlear implant is sold as a kind of cure for deafness, and as a way for the Deaf child to learn to speak and be integrated into the hearing world. Well, that Deaf child — every Deaf child — is born with a history and a cultural legacy of the Deaf community, and I feel that they need access to that community. So I think — I’m pro the choice for cochlear implants because it does… there’s a lot of research to suggest that it does facilitate the acquisition of spoken language skills for Deaf children. But I’m all for bilingual education. You give Deaf children the choice. You give Deaf children the option to do both. So you give them sign language, access to sign languages from early childhood as well, because you never know what that Deaf child is going to choose in the future. And if you give them access to a sign language and to a spoken language, they never have to choose. They have access to both worlds, both communities, both languages, both communication modes, and you know, we know that bilingualism has lots of cognitive benefits. So why not go for it?

DANIEL: That’s true! Okay, great advice! Adam Schembri, thank you so much for sharing your knowledge about sign languages with me today.

ADAM: Thank you for having me.

Patreon supporters

We’re very grateful for the support from our burgeoning community of patrons, including

Jerry

Anthony

Christopher

Adam

Beks

Chris

Christian

Damien

Erica

Erin

JoAnna

Kailyn

Kerstin of the Creative Language Learning Podcast

Mathias

Oleksandr

Sam

Abraham

Bessie

Christy

Iain

kat

Matt

Whitney

and the podcast Lingthusiasm.

You’re helping us to keep the talk happening!

We’re Because Language now, and you can become a Patreon supporter!

Depending on your level, you can get bonus episodes, mailouts, shoutouts, come to live episodes, and of course have membership in our Discord community.

Show notes

One of world’s most prominent Scrabble players banned temporarily for cheating

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/11/14/one-of-worlds-most-prominent-scrabble-players-banned-temporarily-cheating/

U.S. toymaker Hasbro makes new approach to buy Mattel: source

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mattel-m-a-hasbro/u-s-toymaker-hasbro-makes-new-approach-to-buy-mattel-source-idUSKBN1DA2WV

Achcha! Indian English in Oxford Dictionaries

https://blog.oxfohttps://twitter.com/OxfordWords/status/930752254730149888rddictionaries.com/2017/10/05/indian-english-oxford-dictionaries/

Hindi Word of the Year 2017

https://hi.oxforddictionaries.com/hindi-word-of-the-year

Oxford Introduces First-Ever Hindi Word of the Year

https://www.thequint.com/news/education/oxford-introduces-hindi-word-of-the-year

70 Indian Words Make It To Oxford Dictionary This Year. Here’s A Comprehensive List

https://www.scoopwhoop.com/as-70-indian-words-make-it-to-oxford-dictionary-heres-how-it-chooses-its-words/#.46gqt9h15

Automatic sign language translators turn signing into text

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2133451-automatic-sign-language-translators-turn-signing-into-text/

Why Sign-Language Gloves Don’t Help Deaf People

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/11/why-sign-language-gloves-dont-help-deaf-people/545441/

Same-sex marriage survey: 61.6 yes, 38.4 no

https://www.pollbludger.net/2017/11/15/sex-marriage-survey-61-6-yes-38-4-no/

Image credit: https://i0.wp.com/cdn.makezine.com/uploads/2012/01/sign_glove.jpg

Transcript

We’re working our way back through the archives. If you think we should prioritise a transcript of this episode, let us know!