Grammar Day is coming soon. Which rules can you safely ignore?

Is it okay for nouns to become verbs and vice versa? What’s wrong with passive voice? And how can you have a healthy grammar outlook?

Daniel, Ben, and Kylie are going back to the books on this episode of Talk the Talk.

Listen to this episode

You can listen to all the episodes of Talk the Talk by pasting this URL into your podlistener.

http://danielmidgley.com/talkthetalk/talk_classic.xmlPromo

Daniel and Jane talk grammar in advance of the show. What rules can you ignore, and why would it be wrong to say “Between you and I”?

In other news, our local hardware store burnt down in a fiery inferno. Where to get paint samples now?

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/17237651

Animation

by the Mystery Animator

Cutting Room Floor

CW: swearing

What’s the deal with cheap / non-existent shipping?

The way people talk about the word ‘decimate’ — killing one person in ten — is it dumb? Daniel and Ben disagree.

In ads, there’s more than just conversion. There’s also the double superlative. It’s everythinger-er!

And Ben and Kylie give their writing advice.

(There’s a 💩 warning on this Cutting Room Floor.)

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/17309461

Patreon supporters

Our Patreon patrons keep us talking! For this episode, we are indebted to:

Termy

Jerry

Matt

Thanks to all our patrons!

We’re Because Language now, and you can become a Patreon supporter!

Depending on your level, you can get bonus episodes, mailouts, shoutouts, come to live episodes, and of course have membership in our Discord community.

Show notes

Neuroscientists discover a brain signal that indicates whether speech has been understood

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/02/180222125736.htm

Broderick, et al.: Electrophysiological Correlates of Semantic Dissimilarity Reflect the Comprehension of Natural, Narrative Speech

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(18)30146-5

Potentially Toxic Levels Of Lead And Other Metals Found In E-Cigarette Vapor

https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertglatter/2018/02/23/potentially-toxic-levels-of-lead-and-other-metals-found-in-e-cigarette-vapor-study-finds/#7333ba757dcc

NASA reports the Moon’s Water maybe widely distributed across the Surface

http://www.clarksvilleonline.com/2018/02/25/nasa-reports-moons-water-maybe-widely-distributed-across-surface/

John E. McIntyre: Prepare yourself for National Grammar Day

http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/language-blog/bal-prepare-yourself-for-national-grammar-day-20150227-story.html

Steven Pinker: ‘Many of the alleged rules of writing are actually superstitions’

https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2015/oct/06/steven-pinker-alleged-rules-of-writing-superstitions

Superstitions

http://drmarkwomack.com/a-writing-handbook/superstitions/

A Word, Please: Superstitions of the grammatical kind

http://www.latimes.com/tn-dpt-me-0306-casagrande-20140304-story.html

Grammar Superstitions: The Never-Never Rules (PDF)

https://wac.colostate.edu/books/grammar/chapter6.pdf

Grammar Girl: Can I Start a Sentence with a Conjunction?

https://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/grammar/can-i-start-a-sentence-with-a-conjunction

Does Verbing Impact the Language?

http://blog.editors.ca/?p=4679

How Long Have We Been Avoiding The Passive, And Why?

http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/myl/languagelog/archives/003380.html

Stroppy Editor: What’s wrong with the passive voice?

https://stroppyeditor.wordpress.com/2013/07/02/whats-wrong-with-the-passive-voice/

Robert Lowth’s ‘A short introduction to English grammar’, 1799.

https://archive.org/details/shortintroductio00lowtrich

Geoff Pullum: Fear and Loathing of the English Passive (PDF)

http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/~gpullum/passive_loathing.pdf

To Split or to Not Split?: The Split Infinitive Past and Present

http://linguistics-research-digest.blogspot.com.au/2013/06/to-split-or-to-not-split-split.html

Crisis actors, deep state, false flag: the rise of conspiracy theory code words

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/21/crisis-actors-deep-state-false-flag-the-rise-of-conspiracy-theory-code-words

Marco Rubio finally went to a town hall meeting, which is his job, and was aptly roasted

https://www.orlandoweekly.com/Blogs/archives/2018/02/22/marco-rubio-finally-went-to-a-town-hall-meeting-which-is-his-job-and-was-aptly-roasted

How rightwing media is already attacking Florida teens speaking out

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/20/how-rightwing-media-is-already-attacking-florida-teens-speaking-out

Crisis Actors Uncovered?

https://www.snopes.com/same-girl-crying-now-oregon/

Donald Trump Jr. Liked Tweets Promoting A Conspiracy Theory About A Florida Shooting Survivor

https://www.buzzfeed.com/tasneemnashrulla/donald-trump-jr-conspiracy-theory-florida-shooting-survivor

Where the ‘Crisis Actor’ Conspiracy Theory Comes From

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/pammy8/what-is-a-crisis-actor-conspiracy-theory-explanation-parkland-shooting-sandy-hook

Facebook and Google Struggle to Squelch ‘Crisis Actor’ Posts

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/23/technology/trolls-step-ahead-facebook-youtube-florida-shooting.html

‘Crisis Actor’ Isn’t a New Smear. The Idea Goes Back to the Civil War Era.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/24/us/crisis-actors-florida-shooting.html

Donald Trump: Is there a ‘deep state’ in America and is it trying to take down the President?

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-09/donald-trump-is-there-a-deep-state-in-america/8327826

There Is No Deep State

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/20/there-is-no-deep-state

Coup Clucks Clan: Rightbloggers Blame ‘Deep State’ for Trump’s Woes

https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/08/07/coup-clucks-clan-rightbloggers-blame-deep-state-for-trumps-woes/

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

[MUSIC]

DANIEL: Hello, and welcome to this episode of Talk the Talk, RTRFM’s weekly show about linguistics, the science of language. For the next hour, we’re going to be bringing you language news, language myths, and some great music. Maybe we’ll even hear from you. My name’s Daniel Midgley. I’m here with Ben Ainslie.

BEN: Good morning.

DANIEL: And Kylie Sturgess.

KYLIE: G’day, everyone.

DANIEL: On this episode, we’re talking about grammar rules. Should you be concerned about them? Is it okay for nouns to become verbs and vice versa? What’s wrong with passive voice? Some rules are just made up, but they can tell us interesting things about language and the history of English. We’re going to explore them on this episode of Talk the Talk.

BEN: Gee, I feel so animated this week.

KYLIE: Wasn’t it beautiful? I love those vi — I’m so glad so many people have being checking them out on our social media. Those are amazing.

BEN: For listeners who might not be aware, a particularly enthusiastic listener has animated small segments of our show.

DANIEL: And we’re pretty cute in these segments too.

KYLIE: I immediately made it my profile pic on Facebook. So beautiful.

DANIEL: Yes, I noticed.

BEN: If I were to use the parlance, I believe we have been chibi-fied. We are chibi in, like, anime language.

DANIEL: Oh, I like that. Gosh.

KYLIE: So cute.

BEN: I eagerly await more animated tidbits.

DANIEL: I do too.

KYLIE: If not by them, maybe it might inspire other people. I’m hoping that this starts a trend.

DANIEL: Derivative works.

KYLIE: Yes.

BEN: But wax lyrical about animation I can do all day, but we’ve got some news to get through. Daniel, what’s been going on in the world of linguistics in the week gone past?

DANIEL: I ran across a really interesting story coming from the world of neurolinguistics.

BEN: We love neurolinguistics.

DANIEL: A little too much. I wonder if I’m hitting it too hard.

BEN: No, you lay it on me.

DANIEL: I look like the hungry child through the window at the feasting family.

BEN: Nose pressed up against the glass.

DANIEL: Let me ask a question. This is kind of a deep question. What does it mean to understand language?

BEN: Ooo.

DANIEL: Maybe a better question. Let me ask an easier question. Can you tell when someone has misunderstood you?

KYLIE: Well, yes, generally they give physical cues.

DANIEL: Like what?

KYLIE: They go, “aroo?” [CONFUSED DOG HEAD TILT NOISE]

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: So the head tilts.

BEN: Yeah, not always would be my answer. I’ve certainly had students that, months down the line, I’ve kind of gone, “Oh, yeah, we’ve we’ve been operating on different different wavelengths for a while now.” Like, I’ve had — and I’m sure we all have — a misunderstanding come to light much further down the trail and you’re just like, “Ohh.”

DANIEL: I’ve had this discussion lots of times. My partner will say, “Why don’t you tell me when you don’t understand me?” But…

KYLIE: Because I thought I did!

BEN: Yeah, that’s the thing, right? You can’t know what you don’t know.

DANIEL: All right, but when it comes to light immediately, as it often does, how did you know the person didn’t understand you?

BEN: Well, like Kylie said, there could be a range of nonverbal cues. There could be the very obvious verbal cue of the person saying “I don’t understand.”

DANIEL: Could be.

KYLIE: Or they try to tell you back what they thought it meant, and you realise, “No, you’ve got the wrong end of the stick all together.”

DANIEL: I like to imagine that we’re all constructing a picture of what’s going on in our heads while someone’s talking.

BEN: Mhm.

DANIEL: And sometimes it will come to light that the two pictures that we have — my picture and your picture — just do not match.

BEN: We have picture dissonance.

DANIEL: We have diverged.

KYLIE: I had an example where Pamela Gay the astronomer was going to lectures with the rest of the astronomy group that she was with, and the professor kept talking about this symbol called Zed. And all the astronomers were like, “We’ve never heard of — oh. Is this an interesting new kind of symbol?” And they were like looking around, and going through the books.

DANIEL: What is the Zed?

KYLIE: And then they realised about two weeks later that it was actually what the USAans call zee.

DANIEL: Just a Z.

[LAUGHTER]

KYLIE: “Is this something they forgot to tell us, you know, in quantum physics? What?”

DANIEL: The mysterious Zed.

BEN: It does, to be fair to Americans, it does sound like an off-brand bad guy from a superhero film. Right? Like Zod was busy, so they got in Zed. You know…

DANIEL: Zod’s brother.

KYLIE: We continue to look for Zed. You know he’s out there somewhere.

BEN: Anyone who does the ABCs and ends in a zed feels the inherent weirdness of that letter. Like X Y Zed. It doesn’t work.

DANIEL: Now, if you were a neuroscientist, and you wanted to look for some kind of brain signal that someone had misunderstood, what would you look for?

BEN: Oh, dang! I am going to say that this is like the language thing where understanding is not a thing. There’s no, like, magical little bull’s-eye that you can just [BOW AND ARROW SOUND EFFECT] and just find it and measure it, and if understanding has happened that bit fires off. I reckon it’s like a big, like one of those houses where people spend way too much money on Christmas lights, and there’s like eleven different programs, and they can all go off in different ways. I reckon it’s more like that.

KYLIE: And the kids think it’s great, but yeah the adults are like, “Oh, geez.”

BEN: It’s like a CHRISTMAS RAVE! I reckon it’s a Christmas rave in people’s heads when they understand it.

DANIEL: What do you think, Kylie?

KYLIE: I think we make connections. When we understand something, we link it to prior knowledge. So if you were looking at the brain patterns, maybe there would be gaps. It’s not clicking and linking, like blocks of lego.

BEN: Dead ends. I’m hearing dead ends.

KYLIE: So it’s like… PLINK! like, you know, one lego brick falling, and none of the other lego bricks hooking up to it.

DANIEL: Okay, well, the story here is that neuroscientists have discovered such a brain signal that indicates whether speech has been understood.

BEN: Oh, so there is a target! There’s a bulls-eye!

KYLIE: So, there is a signal like, “Aroo?”

DANIEL: Well, let me describe what it is. This is work by Michael Broderick and a team from Trinity College Dublin. They got volunteers to listen to audiobooks — other work used made-up sentences, but this is just straight from the stream — and then they used and EEG to measure the brain patterns of the volunteers while they were listening.

BEN: Mhm.

DANIEL: The thing about words is that some words are semantically related to other words, and other ones not so much. Let me demonstrate. I picked out two news stories — just very short news items — and I’m not going to tell you when one story switches to the other story. You have to just tell me to stop.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: The next time you inhale the vapor of an e-cigarettes, consider this: there may be toxic levels of metals, including lead, that could be leaking from the heating coils of your device. A new analysis of data from two lunar missions…

KYLIE: THERE! HA HAA! I win!

BEN: How did you do it, Kylie?

DANIEL: You noticed at the word ‘lunar’.

KYLIE: Yeah, yeah, it was the word ‘lunar’. It was like ‘smoking’ and ‘lunar’ — what?

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: ‘Lunar’ is not related to the words ‘vaping’ or ‘smoking’ or anything like that. At some point, it changed to words that had no semantic relation, and then when that happened you noticed.

BEN: Yep.

DANIEL: So these experimenters measured brain activity, and they matched it to the semantic similarity of the words that they were listening to. They were using a technique that helped them to know that ‘lunar’ and ‘e-cigarettes’ were not related really very highly.

BEN: Go over that bit again. So, what they were deploying was deliberately using semantic breaks like the one you just demonstrated to measure what, like… ‘huh?’ looks like in the brain.

DANIEL: That’s it, and the place that went ‘huh?’ was in the centro-parietal region.

BEN: Oh, the old centro-parietal region. You old dog!

DANIEL: Oh, you know a lot about that region, do you?

KYLIE: It’s at the front here, at the front. That’s the pre-occipital lobe, so it’s up here.

DANIEL: And do you know what it does?

KYLIE: Um…

BEN: It totally tells researches whether you’ve understood something or not!

DANIEL: Apparently!

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Whoa! Two accidental wins in a row!

DANIEL: It’s a place where lots of inputs come together and it’s pretty important for language processing.

BEN: It’s a hub.

KYLIE: It’s a hub. When people get, yeah, the front of their head smacked into like when I [ahem] fell down the stairs of the Cultural Center, for example, yeah, I ended up feeling myself quite muddled in terms of what I had to say.

DANIEL: Oh. Oh, gosh.

KYLIE: Because I had a concussion. But yeah, that’s a biggie for people who get hit there.

DANIEL: So they noticed a correlation between semantically not-as-related words and brain activity in that region. They also gave them a test afterwards to see if they really had understood. And so, putting all that together, they found a very clear signal for when the volunteers noticed semantically unrelated words, which is tied to understanding.

BEN: So if I’ve got you right, they didn’t so much identify what understanding looks like. They identified what the ‘huh?’ moment looks life. Right? So, which is not necessarily the same thing. So they’re not seeing a clear signal of what understanding is, but they are seeing a clear signal of what understanding isn’t. What not-understanding is.

DANIEL: That is a really interesting point, and there was something else that this made me think of. They were able to measure comprehension — or non-comprehension, as the case may be. But that’s not quite the same as noticing when words are semantically unrelated. It’s a bit more complex than following a chain of words. It’s also following a chain of meaning, and a chain of inference. Sentences can be ambiguous like the famous: “Would you like some coffee?” “Coffee might keep me awake.” That could be a refusal.

BEN and KYLIE: Yeah.

DANIEL: Or it could be a good idea. And another thing is that implication is an important part of understanding. Like if I say, “Unlike SOME people I could mention!” I would love to know how to model this kind of understanding, but until then, this is an interesting look at what the brain is doing when words are going past in real time.

BEN: The brain be cray. Like straight up. Just… just mapping the brain with all of the words that we have for the brain already loses ninety nine percent of the population, right? As soon as you get, like, more than three region names in, people are just like [COMPUTER SHUTDOWN NOISE] BYOOOOOOOP. Like you just switch off! You do!

DANIEL: It takes practice.

BEN: The brain is nuts, man!

KYLIE: It’s the wonderful thing about it. We’ve all got one. Er, well, I hope we all have one, because we’re listening to the radio right now. But it’s just so fantastic and we keep learning new things about it and that’s that’s what makes it so extra special.

BEN: Well, I’m going to have to ruminate on understanding for a while. Should we take a track?

DANIEL: Yes, let’s listen to Husband with ‘Understand’ on RTRFM 92.1.

[MUSIC]

BEN: This week on Talk the Talk, we are delving into matters of grammar. That very favorite thing that everyone totally remembers from primary school, not really at all.

DANIEL: Not really at all.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: I think it causes people a lot of distress, which is why there’s Grammar Day coming up.

BEN: Oh, that could be the best and the worst thing ever.

KYLIE: Are we going to wear, like, t-shirts and something? Or come up with slogans?

BEN: No, but you know what, you… YOU, Daniel… I’m pointing at Daniel right now.

KYLIE: Yeah, oh, he’s jumping up and down.

DANIEL: You, Daniel, know what my fear is here, because you do a show on the ABC, so you know what some people are capable of. Right? And if someone hears, “Oh, it’s Grammar Day,” they’re going to have a very different connection to that statement.

KYLIE: [OLD WOMAN VOICE] This is Disgusted of Dalkeith phoning up again for that American who thinks he knows everything about the English! What’s he telling the Australians?

BEN: Oh, no. Goddamn it, I’ve got to stop mentioning the ABC. She trots her out every time!

KYLIE: Aughhh…

DANIEL: You know, it’s coming up on March 4th, which is Sunday, I believe. And so this is prime time to start talking about grammar rules. We have already talked about grammar, and is it elitist? That was show number 300. Some of the grammar rules that people have are just really pointless and silly. There’s the one about ‘decimate’.

BEN: Oh, yeah, like you… you technically can’t use it because it actually only means killing one in every ten people.

DANIEL: But of course, that’s not how the word got that way anyway.

BEN: Oh.

DANIEL: Here’s another one from the AP Style Guide on the word ‘collide’. “Two objects must be in motion before they can collide.

A moving train cannot collide with a stopped train.”

KYLIE: Oh, wow!

BEN: Boo! Boo boo boo.

DANIEL: That is dumb, and they are committing the etymological fallacy. A word doesn’t mean what it used to mean. Also ‘dilapidated’. Can a wooden house be dilapidated?

BEN: Uh, yeah.

DANIEL: You’d think so. But if somebody were being a grammar crank, they would say no no no. ‘Lapid’ means stone. Only a stone house can be dilapidated.

BEN: Oh my god, that’s like next level d-baggery!

KYLIE: Like ‘lapiz’. Oh, I get it.

DANIEL: And yes, I do realise that these peeves are not strictly about grammar. They’re more about semantics. But I’m kind of lumping all the language peeves into grammar in this case, so just be aware of that. Well, Kylie, you got me on this topic because you pointed out to me something that really bugs you. Would you like to…

BEN: Kylie, did you get your grammar grouch on?

KYLIE: It’s something that’s bothered me for a while. When I was a…

BEN: I would have thought, after this many years of Talk the Talk, you would be above this, Kylie! Come on, name and shame. What’s your gripe?

BEN: It’s just something I keep noticing, strangely enough, around Perth. But this goes back to the day when I was a radio student, and one of the other students in the class, when we had to come up with a slogan for our student radio station, kept on saying “Sounds of awesome! Sounds of awesome!” And it irritated the bejeezus out of me! because it didn’t seem to make sense.

BEN: Pause. Pause, pause, pause. First of all you were definitely that kid in school. Second of all.

KYLIE: It was just irrita— I think it was because she kept on going on and on.

BEN: Sounds of awesome. I actually kind of like that! Look, don’t get me wrong.

KYLIE: GRRRRR

BEN: To sit in a round table at a marketing pitch meeting and that was floated, it would definitely not be going on the top of my list. But at the same time: ‘Sounds of awesome’… like the tinkling sounds of awesome emanating from the speakers.

KYLIE: NO

BEN: I’m on board.

KYLIE: NOO

BEN: What is your gripe? What is your actual problem, though?

DANIEL: Can we describe what is wrong with this, grammatically?

KYLIE: She’s using ‘awesome’, which is an adjective, and she was trying to use it as a noun.

DANIEL: Right. Okay.

BEN: The sounds of awesome, awesome being a thing.

DANIEL: Yeah, she was trying to sort of convert that. I heard a lot of examples of this watching the Olympics, and one of the announcers said “It’s a solid run, but is it enough to podium?”

KYLIE: Yes!

DANIEL: Okay?

BEN: So good.

DANIEL: I know!

BEN: So good. I’m so on board with this!

KYLIE: No, no!

DANIEL: ‘Podium’ is a noun. It’s a thing, right?

KYLIE: Yeah.

DANIEL: But this person was taking it and using it like a verb.

BEN: Yep.

DANIEL: To podium. And don’t forget: also, ‘run’, you know.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: ‘Run’ we think of as a verb, but here it’s being used as a noun.

KYLIE: You had a good run. Yeah.

BEN: It’s a solid run.

KYLIE: Yes, and it’s not something that’s unusual. It’s just sometimes it really grates on me. And there’s a long history of it. Shakespeare has done it. If you have a look at Hamlet: “My sea gown scarfed about me.” “Dog them at the heels.” “Season your admiration.” You know, it’s probably just as bad as the… “Season your admiration: try the chicken!”

BEN: Well, if it’s good enough for old Bill, like, what’s up?

DANIEL: I noticed this with the UWA slogan a while back: Pursue Impossible, which I think we talked about on the show.

BEN: It’s… look, it’s good marketing insofar that it’s, like, ambiguous enough to be entirely meaningless, but yet vaguely aspirational.

DANIEL: Doesn’t your university do this as well with their slogan?

KYLIE: Well, that’s the thing. I’ve got something for the both of you. Have a look at some of these, and tell me if any of these grate on you because I know what it is. It’s something called ‘anthimiria’, where you get one particular part of speech or sentence, and it’s been flipped over to use something else. So verbs as nouns, adjectives as verbs.

DANIEL: I’ve heard a lot of names for this process. Some people call it ‘conversion’.

KYLIE: Yep, that’s another one.

DANIEL: Some people call it ‘nominalisation’, or verbing if it’s going the other way.

KYLIE: ‘Zero derivation’ is another way of calling it.

BEN: Oh, that’s fun. That’s sci-fi.

DANIEL: That’s a good one. Because you’re not adding anything like -ment as in ‘development’, or…

BEN: Zero derivation.

DANIEL: Yeah. You’re just taking that noun, not adding anything, making a verb.

KYLIE: So you’re going to see a lot of it in advertising. People trying to mash it up.

BEN: It’s vaguely poetic, isn’t it? You take this noun and you create a verby verby verb out of it! Because a scarf, right, is such a idiosyncratic noun, right? A scarf is a scarf, and so ‘to scarf around you’ is just so evocative.

DANIEL and KYLIE: Mmm!

KYLIE: Have a look at these, guys, and tell me if any of them jump out to you as “hey, that’s useful” — “hey, that’s crap.”

BEN: Should we do it one at a time?

DANIEL: Sure, you go ahead.

BEN: I’ve got a couple of ‘fabulous’ ones, so I’ll run through them. So from Thai Tourism, “Find your fabulous.” From California Lottery, “Go directly to fabulous.” ULTA: “Welcome to fabulous.” And Mindtree, “Welcome to possible.”

DANIEL: Nutella had “Spread the happy.”

KYLIE: Ugh! [LAUGHTER] You see, some of them just make you go ugh!

DANIEL: I wasn’t sure about that one. There was Sungevity with: “Generate positive.” Not ‘positivity’, but ‘positive’. And Xfinity with “The future of awesome.” Hey, they took her slogan.

KYLIE: I know. Awful exists everywhere.

BEN: You know what, I actually frickin’ love this one: “Would you let me see beneath your beautiful?”

DANIEL: That was a song.

KYLIE: No!

BEN: I love it.

KYLIE: Labyrinth. It’s a song by Labyrinth.

BEN: Especially in our idiom of Instagrammed falsery, that I think has become ever more relevant.

DANIEL: Hmm. And then Carvel has “It’s what happy tastes like.” Not what ‘happiness’ tastes like, but what ‘happy’ tastes like.

BEN: I’m… see, I’m fine with that because I’m like, “okay, happy’s a thing and it has a taste.” I’m down.

DANIEL: I find that that one is a little bit more acceptable than this one from Fiat: “Unlock your more.”

BEN: Yeah, that’s just… it’s too ambiguous.

DANIEL: ‘More’ seems… what is ‘more’ anyway?

BEN: More is SO vague though, isn’t it? Like ‘more’ can be so much better and so much worse.

DANIEL: Is it Roger Moore? What is… what is ‘more’ as a part of speech?

BEN: More is a multiplier?

KYLIE: Yeah, it’s amounts, isn’t it?

DANIEL: Okay, so what part of speech does that?

BEN: It’s not a verb.

DANIEL: It’s not a verb.

BEN: It’s not an adjective.

KYLIE: A nominal?

DANIEL: I want to ‘more’ some pizza? No.

KYLIE: No, no!

DANIEL: It’s not a noun, because…

BEN: I want more.

DANIEL: So what is that doing?

BEN: I want more water. I want more love.

DANIEL: Mmm. It’s being a quantifier.

KYLIE: Quantifier. That’s it.

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: Okay! Interesting, so — wow, what an interesting lot of slogans. And your feels about this are strained?

KYLIE: [DEEP BREATH]

BEN: WHY? Why do you care? We have spent so much time…

KYLIE: It’s just jarring at times. It’s really jarring at times, and I think to myself, you know, must I really ‘free my think’ or…?

DANIEL: You know what? I’m glad that this has come out, Kylie. Thank you for sharing this with us.

KYLIE: I’m not so sure if I really enjoyed where it went, but anyway.

DANIEL: That’s all right. I feel like there are three phases that all of us need to go on, and I’m kind of borrowing this from Grant Barrett of ‘A Way with Words’. But Phase 1 is where you say “Ugh! I hate when people say thing!”

BEN: Yup.

DANIEL: Phase 2 is sort of like “I know I should not hate when people say thing but I still kind of do.”

BEN: Kylie’s there.

KYLIE: That’s me! Phase 2! Phase 2 girl.

DANIEL: Nice! Good! You’re almost there. And then…

KYLIE: Oh man, do I have to…?

BEN: Brutal.

DANIEL: Phase 3 is like “I think it’s kind of cool when people say thing.” Or even better: “I wonder what people are trying to accomplish when they say thing.” That’s when you’re asking interesting questions. So.

BEN: Yeah, I just… I dig it. I just… all the funny changes that have come our way of late have just been really fun. Have been really delightfully fun.

DANIEL: There’s nothing wrong with nouns becoming verbs, or verbs coming nouns…

BEN: Unless you’re Kylie.

KYLIE: Thanks, yeah. Pick, pick, pick, pick.

DANIEL: English has a long history of flexibility with parts of speech, and in fact it’s not even easy sometimes to tell which one came from which. I wonder if the two of you can tell me…

BEN: Oh… SHIT! WE KNOW WHAT THIS IS!!!

DANIEL: …whether these words were first nouns or first verbs.

BEN: [IMPROVISES EXCITING MUSIC] I love a good competition.

DANIEL: Are you ready?

BEN: Yep.

KYLIE: Okay.

DANIEL: Okay, think to yourselves: was this a verb first or a noun first? Impact.

BEN: Verb.

DANIEL: Kylie?

KYLIE: I’ll go noun.

DANIEL: Ben has the point. [DING]

BEN: Yesss.

KYLIE: Well done.

DANIEL: You could impact a thing — that’s the verb — round about the 1600s, but something had impact — the noun — no sooner than 1738.

KYLIE: Wow.

BEN: There you go.

DANIEL: Okay, how about this one, noun or verb: access. Which came earlier, that you could access something, or you had access to something?

BEN: Uh, I’m going to go verb again.

KYLIE: Had access to something. Noun.

DANIEL: So it sounds like you think that the noun is the earlier one. Kylie takes this one! [DING]

BEN: Ooo!

DANIEL: You could have access around the early fourteenth century.

BEN: Wow.

DANIEL: But as a verb, to access something: only since 1962, as far as we know.

BEN: Dang!

DANIEL: Yeah. How about ‘inconvenience’? I hate to inconvenience you — the verb. Or it’s such an inconvenience — the noun. Which one came first?

KYLIE: Verb.

BEN: Um… no, I’m going to go noun.

DANIEL: The inconvenience?

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Ben takes the point! [DING]

BEN: Yeah!

KYLIE: Well done.

DANIEL: Two to one.

BEN: It’s just… it’s too… This might be a very silly thing that I just did in my head, but it strikes me that verbs tend to be a bit shorter.

DANIEL: Interesting!

BEN: Whereas in-con-ven-i-ence… like, there’s not a lot of five syllable words in English really — not in regular usage.

DANIEL: Interesting, well, let’s…

KYLIE: Let’s test it with the next one.

DANIEL: Okay, the word is ‘quiz’.

BEN: Welp, I feel like I’ve kind of hoisted myself on my own petard here, so I’m going to go with verb!

DANIEL: Kylie, do you like verb or noun? To quiz somebody, or to have a quiz.

BEN: Let’s try verb.

DANIEL: You both make the point! [DING]

KYLIE: Yay!

BEN: Yesss.

DANIEL: But it’s a very narrow one. You could quiz somebody from about 1847, but you would take a quiz around 1852. Very soon after. Demand. Do you think that you made a demand, or do you think that you could demand something first?

BEN: I’m going to let Kylie answer this one first.

KYLIE: Demand something first.

BEN: Demand… no, I’m going to say noun.

DANIEL: Ben takes it! [DING]

BEN: Yeah!

KYLIE: Well done!

DANIEL: Okay, so…

BEN: It sounded very French, and they’re very nouny people.

DANIEL: It could be a question from the late thirteenth century, but you demand things round about the late fourteenth century. Well, let’s see, I’ve got one more here. Kylie, this is your chance to tie it up.

KYLIE: Okay.

DANIEL: This one’s a fun one. Orange. Which came first — orange the colour, or orange the fruit? We’re talking adjective versus noun here.

KYLIE: Ben’s wiggling in his chair in discomfort.

DANIEL: Kylie, you first. Which came first: orange the colour, or orange the fruit?

BEN: Colour.

KYLIE: Fruit.

DANIEL: Fruit it is! [FANFARE]

BEN: Come on! Really?

DANIEL: Yes, it turns out the word was ‘narancia’.

BEN: ‘Naranja’ is Spanish.

KYLIE: I see it on those little bottles of juice sometimes.

DANIEL: The fruit came about around the 1300s, but we wouldn’t see the colour orange until 1540ish.

BEN: I can’t believe that…

KYLIE: Colours are weird! They come a lot later, don’t they?

BEN: That’s really bizarre to me though, because I thought for sure I had it locked up with just the fact that that food didn’t hit Europe for a while. I thought it might be like potatoes and that. But actually, if it’s in the 1300s, that’s in Europe a lot earlier than I thought it would be.

DANIEL: I actually had a hard time finding words for this quiz because so many words arose as nouns and verbs in Old English at the same time.

BEN: Simultaneously.

DANIEL: Like ‘plant’ and ‘walk’ and ‘book’ and ‘love’. And you know, why wouldn’t they? I mean, why invent two separate words for closely related things?

BEN: It is pretty dumb.

DANIEL: Well, well done. It was a tie, but the point is: there’s no point getting worked up over conversion or zero derivation because it can be really difficult to tell the difference. That’s just how English goes. So instead of peeving, maybe a better idea would be to start thinking about what they were trying to do by saying that. When you ask yourself “I wonder what this can tell me about language”, then you’re very close to Stage 3. And you find yourself looking forward to the next opportunity. But now I think we need to take a track. This one is Orbital with ‘Impact (The Earth Is Burning)’ on RTRFM 92.1. Remember, if you have any questions or comments about anything you hear, why don’t you get those to us? talkthetalk@rtrfm.com.au

BEN: You can tweet us @talkrtr. And of course, we have a wonderful page where people on Facebook — and animators on Facebook — can share all sorts of great fun ideas and thoughts and feelings and mmm — it’s just a great time.

[MUSIC]

BEN: On this show, we are allowing Kylie the space to get all of her grammar grouchiness out on the table.

KYLIE: Oh sure, just pick on me.

BEN: Hey — you’re the one who brought the hell-fire to the show! You were like, “I’ve got a complaint to make!”

KYLIE: ‘Sounds like awesome’. Yeah.

DANIEL: But I’m glad that we heard it though, because you know you’ve got to get these things out in the open. It’s a supportive environment.

BEN: Unless people break grammar rules, in which case it’s: SurPRAAAHHHHH!

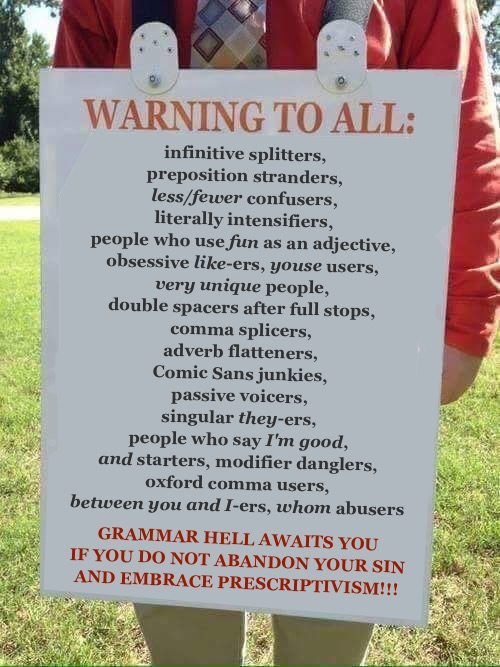

DANIEL: Grammar Day is on March 4th, and I just thought we could take the roll call of language pedants in the past, and the silly grammar rules they invented.

BEN: Oh, yay!

DANIEL: We’ve already talked about Robert Baker, who decided that ‘less’ and ‘fewer’ were a thing.

BEN: Ugh! People still bang on about this.

DANIEL: It’s weird, isn’t it? Another one: John Dryden, the poet who decided that he was not going to end sentences with propositions anymore. He wasn’t going to end them with ‘of’ or ‘to’. He was going to rework his poems to get rid of all those stranded propositions at the end of sentences.

BEN: Who did the: “you can’t start a sentence with ‘because'”? Because I got a major beef with this person. I assume it’s a dude. I got a major beef with this dude.

DANIEL: The one I’ve heard is starting a sentence with ‘and’ or ‘but’. And what I’ve noticed is that just about nobody really cares about that. Even the crustiest style guides call this a superstition.

BEN: Ah, okay.

DANIEL: It seems to have been during the nineteenth century. It seems to have originated with schoolteachers who thought that students were beginning sentences with ‘and’ or ‘but’ too much, and so they put a blanket ban on it. And some people believed it, and that worked its way into a grammar superstition. But it’s okay. I’m a big and-er at the beginning of sentences. Absolutely huge. I do it a lot.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: Jonathan Swift, the writer.

BEN: Right, as in…

DANIEL and KYLIE: ‘Gulliver’s Travels’!

BEN: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: He was a humorless pedant. He hated new words. He didn’t like clipping the ends of words, and he also wanted to establish an academy of English so that they could stop language change.

BEN: Oh, good. Just like the French.

DANIEL: Then there was Robert Lowth, who in 1762 wrote A Short Introduction to English Grammar. Enormously popular. He hated double negatives.

BEN: Would you have said that he… Lowthed it?

DANIEL: I think I might. He said, “Two negatives in English destroy one another, or are equivalent to an affirmative.” He’s the guy behind the double negative.

BEN: Ugh!

DANIEL: And he hated ending sentences with propositions like ‘of’ or ‘to’, as well. And then there’s that funny old rule about the split infinitive.

BEN: What is a split infinitive? Catch me up.

KYLIE: To boldly go where no man has gone before.

DANIEL: That’s it.

BEN: I don’t get it.

DANIEL: The infinitive form is ‘to go’, ‘to do’, anything with ‘to’ in it.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: Now the idea was that you shouldn’t stick any words between the ‘to’ the ‘go’. That was probably because people thought that Latin was the coolest language in the entire world.

BEN: Oh, but it really wasn’t.

DANIEL: It really wasn’t, no.

KYLIE: I think we agree on that.

BEN: Super wacky rules.

DANIEL: But the thing with Latin is that the infinitive forms are just one word.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: You can’t stick anything in the middle.

BEN: Gotcha.

DANIEL: So there’s this person who, in a letter to the New England Magazine in 1834 — they signed themselves only as P, the letter P — they said that they don’t know any rules against splitting your infinitives, but they didn’t like it. They didn’t like it one bit.

BEN: “I don’t care for these split infinitives at all!”

DANIEL: Now, there was a market for this stuff. Because of the Industrial Revolution, some people were becoming very very wealthy and they wanted to separate themselves from the working classes, including in language. So they were just looking for all kinds of ways that they could…

BEN: Right, just… almost… it’s verbal table manners. Right? Like, let’s construct a set of rules — highly specific, highly difficult to remember set of rules — that we will teach our children, but other idiot children won’t know. Ma-ha-ha-haa!

DANIEL: That’s kind of how it was! They weren’t trying to document English. They were trying to make it the way that they wanted. Our friend Steele on Facebook asks a question: Why do teachers hate passive voice so much?

BEN: I actually have this question as well, because I have noticed that the war against passive voice has actually been ramping up.

DANIEL: Really?

BEN: Yeah.

KYLIE: Really? Huh!

BEN: I’m seeing people whom I respect going through and, like, rewriting their theses and dissertations to just like obliterate passive voice from it entirely, on the behest of some like, “I’m an important writer person, and I reckon passive voice ferrken serrrxx.” And it just like… I don’t get it! I don’t! Can you explain it to me?

DANIEL: Well, let’s first of all talk about what passive voice is. I’m going to give you a sentence in active voice and you turn it passive. Ready?

KYLIE: Ready.

DANIEL: “A snake bit Aunt Alexandra.”

KYLIE: “Aunt Alexandra was bitten by a snake.”

DANIEL: That’s passive. So, what you do is you swap the two participants, and sometimes you can leave out “the snake” entirely. And then you usually add in a form of ‘be’ and a participle, like “was bitten”.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: Okay? Now this aversion to the passive voice is actually kind of a new thing.

BEN: Yeah!

DANIEL: Geoff Pullum, in an article that he wrote — link on our blog, talkthetalkpodcast.com — he points out that nobody mentions it until the twentieth century.

KYLIE: And that’s when Word started doing little squiggly lines underneath all of the little word processing documents, saying “It’s passive voice. Are you sure you don’t want to rephrase it?” No, bugger off, Clippy!

DANIEL: I totally think that Microsoft Word and its hatred of the passive got everybody thinking about it, and like, “Oh, what is passive voice, and why should I write…?” And so, everybody is like, on it now, and that’s why I think this is ramping up.

BEN: It’s very weird because I see zero differentiation. Like when I read something in passive voice, until it was pointed out to me — even with — do you know what it’s like for me? It’s like songs with lyrics. Unless I am, like, leaning all the way forward and really almost studying a song, I don’t hear lyrics. Right? I just don’t ever hear them. And passive and active voice is the same way for me. I’ve had exactly what that is explained to me a bunch of times, often by people who are like, “Stop doing this,” and I go, “Okay, cool, I can identify this.” But to actually hear it in my head as I’m reading it, I would have to lean forward. Like, I would have to really say, “Uh… passive voice! Passive voice.”

DANIEL: Because it sounds fine.

BEN: Because if I just read a book or whatever, it makes no difference at all.

KYLIE: I just keep reminding myself when I’m editing over, I tell myself, “Is it active? Is it action filled?” Are we seeing something happen that goes here instead of, “Oh, she was bitten by the snake.” That sounds floppy to me. The snake bit her!

BEN: But does it only sound floppy to you because you’ve had a series of people you respect tell you that that’s a thing?

KYLIE: I’ve had enough little wiggly lines in my Word documents telling me I’ve got it wrong.

DANIEL: You know it’s possible to have a floppy sentence that isn’t passive voice. For example: “There were many snakebites that day.” You know. It’s a bit floppy. It doesn’t say who’s doing what. But it’s not passive voice. And this is one thing that I think people don’t like about it. You can actually use passive voice to be evasive and shifty.

KYLIE: Bit of weasel words happening.

DANIEL: You can say “Mistakes were made” (but not by me), instead of saying “I made a mistake.” And a lot of people feel like a good sentence should be, you know, somebody doing something.

BEN: Definitive.

DANIEL: But there are lots of times when passive voice just sounds a lot better than active voice. But look, grammar rules, the kind that are delivered from on high, you can often just ignore them.

BEN: They’re nonsense.

DANIEL: You know what, in writing I think this is a weird area because generally when we’re speaking we have instincts about what sounds good, and we just adhere to them. But when we’re in the writing mode, now we feel a little insecure because maybe we don’t have a lot of experience, and writing is a higher-register sort of thing. So we might feel intimidated, and we look to advice from others.

But then we’re sitting ducks for stupid made up superstitions. So in that case, be a good noticer, read a lot so you can absorb the patterns…

KYLIE: Oh, always read a lot! You never know when you’re going to learn something new.

DANIEL: And find a style guide you trust. One of my favourites: Nicolas Hudson’s ‘Modern Australian Usage’. He’s got his head on straight. And you know what — I will soon be releasing a video on Patreon that will show you how to use freely available corpus tools to answer your own questions about grammar.

BEN: Boom. So you can use the software in your head, and you can also use the free software that Daniel provides.

DANIEL: There you go.

BEN: Hey, that’s pretty cool.

DANIEL: Well, I hope you all enjoy International Grammar Day on the fourth of March.

KYLIE: Wear something completely inappropriate on your t-shirt. It’ll be brilliant.

BEN: Emojis.

KYLIE: Yeah!

BEN: Just to really just cheese the pedants off.

DANIEL: Yeah, that would do it.

BEN: Yeah.

DANIEL: Let’s take a track, and this one is the Clientele with ‘Voices in the Mall’ on RTRFM 92.1.

[MUSIC]

BEN: [SOFT HONKING NOISE]

BEN: [SOFT HONKING NOISE AGAIN]

DANIEL: What is this?

BEN: [SOFT HONKING NOISE WITH MODULATION]

BEN: It’s Word of the Week.

KYLIE: I thought it was that peacock coming in to be herded by you again.

DANIEL: I was kind of thinking peacock, as well.

BEN: Well, apparently, according to you guys, peacocks are ferocious, disgusting creatures that make awful sounds, and everyone hates them, so I’m not bringing peafowl up again.

DANIEL: I’m glad we established this.

KYLIE: One of them stole the end of my ice cream at the Perth Writers’ Festival!

BEN: You guys said peacocks. I didn’t even bring it up this time.

DANIEL: That was a lovely solo. Thank you, Ben.

BEN: Thank you.

DANIEL: In the wake of yet another US school shooting, we’re going to take a moment and descend into the fever swamp of the paranoid American right wing.

BEN: Oh, must we?

KYLIE: Sorry.

DANIEL: Well, there are a number of terms that have come out of this week’s event. So there was a school shooting at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. But in the aftermath, a number of survivors — high school students themselves — stepped up as eloquent and passionate critics of US politics and US gun culture.

BEN: I hear watching your friends be murdered by guns will really make you anti-gun.

DANIEL: Yeah, what’s the deal with that?

BEN: Weird.

DANIEL: There was Emma Gonzales, who gave a rip-snorter of a speech in Fort Lauderdale. David Hogg turned out to be a capable spokesman.

Cameron Kasky destroyed Florida senator and part-time ferret Marco Rubio by saying, “Can you tell me right now that you will not accept a single donation from the National Rifle Association?” So the right-wing response has been to go after them, dismissing them as plants and — here’s the term — ‘crisis actors’.

BEN: Cool. So like, just really quickly though, we know that this is an actual thing, right?

DANIEL: Being a crisis actor?

BEN: Yeah, so it’s a job you can do.

DANIEL: Tell me more.

BEN: So when you are learning how to be a police officer, or a firefighter, or even… My particular favorite of this example is a thing that we do here in WA called the Street Smarts program. So what happens is, in our big basketball stadium which seats like fifteen thousand people, the central court gets taken away, right? And every Year 11 student — so like, sixteen-year old student in the metro area — gets brought to this stadium.

KYLIE: Really?

DANIEL: Gosh.

BEN: All the lights go down, right? They hear some funny noises, and then they hear the soundtrack of, like, a horrific screeching metal car crash. Lights come up, and a car that has been in a horrific car crash is now in the middle of the stage. Inside that car are like four young people — actors, crisis actors — who now act out the two-and-a-half–hour-long stage play of what exactly happens.

DANIEL: Wow.

BEN: So this stuff is so heavy, they have psychs in the wings for all the participants who are just, like, traumatised by this. I think it’s amazing. So crisis actors are a thing. They exist.

KYLIE: The closest I’ve ever got to anything like that was first aid training, where we just have a neat sign pinned to our shirt which said, “I hurt my head.” And that was it. And they come up to you with bandages and say, “Oh, you’ve hurt your head.” Or “Oh, broken leg, here we go.” Geez, man!

BEN: So, for people listening, there are actual crisis actors out there and they’re just role players and they do great work.

DANIEL: Okay, well, the right wing in America…

BEN: …Is not talking about these people!

KYLIE: No.

DANIEL: Has picked up this term ‘crisis actor’ and has used it to refer to the young people themselves. One pundit said that David Hogg was “heavily coached on lines and is merely reciting a script.” Others have dismissed them because they’re young. Donald Trump Jr liked two such tweets. By the way, can I just point out that dismissing political opponents as paid shills goes all the way back to the US civil rights struggle.

BEN and KYLIE: Oh, really?

DANIEL: Yes: “Oh, they were driven in from out of town. They were paid.” Etc, etc. This has been going on in America for a long time.

BEN: So we’ve got ‘crisis sector’. Have we got some more?

DANIEL: There’s another one: ‘false flag’.

BEN: Ah. Now, this goes back quite a way, doesn’t it?

DANIEL: Tell me more.

BEN: Well, false flagging is like Age of Sails stuff.

DANIEL: Yes, it is.

BEN: Yeah. So like you’re flying the wrong flag on your boat to try and evade tarrifs, escape notice.

KYLIE: Oh, really?

BEN: Whatever it happens to be.

DANIEL: To get close to an enemy ship under pretext of being with them.

KYLIE: Oh, pirates!

DANIEL: That’s right. And then when you’re just about close to them, then you fly your real flag.

KYLIE: Jolly Roger! Here we go.

DANIEL: Your true colours, right. And then make a false flag attack. So Google searches skyrocketed for this term in April 2013 after the Boston Marathon bombing, where some people started the conspiracy theory that this was a false flag. They claim to be this, but they were actually that. And then there’s this term: ‘deep state’.

BEN: Now, this is interesting. I’ve heard about this before and it’s kind of fringe. Like it’s… even amongst conspiracy theorists, this is like far down the rabbit hole.

KYLIE: So the conspiracy that even the conspiracy theorists go, “Yeah… what?”

DANIEL: Oh, the weird stuff is normal now.

KYLIE: Oh, geez.

DANIEL: The ‘deep state’ refers to US law enforcement, other sorts of government agencies like the military or the intelligence agencies.

Basically, anything that gets in the way of the president. You see, the Trump presidency is shambolic and incoherent, but his followers can’t admit that, so they have to say that the deep state is trying to bring him down. They’re all conspiring against him.

BEN: Like non-elected governmental functionaries, essentially, is the deep state.

KYLIE: Do you think we’ll end up having lizard people being to blame? I want lizard people, because then everything is just going to go ‘snap’.

BEN: I gotta be straight up with Donny T as president — that actually is a conspiracy theory I’m closer to accepting.

DANIEL: I’m up for anything at this point.

BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Kylie, as a skeptic, can you give me any insight as to why people would need to invent conspiracy theories or why they love them so much?

KYLIE: People invent conspiracy theories for many different reasons. One of the big ones is a feeling of control. You also get a feeling of community. You get a sense of unity that’s occurring when people share this particular belief.

BEN: I know what’s really going on.

KYLIE: A sense of comfort. It also gives you a goal, as well. You as a community that now feels like you’re in control of something says, “Right, well, now we’ve got something to fight against or act for, or prevent happening, due to this conspiracy.” And we can all be subject to these things. We all look for patterns. We all look for sources that will confirm our biases that we have out there. But when you’ve got a lot of people around you saying, “Why, yes, that’s true, president! And let’s all tweet in unison in regards to it,” it’s going to become quite solid. And unfortunately, anything that seems to challenge it can be seen as fueling that conspiracy, as well. So it takes a lot of effort to break these things down.

BEN: I would a hundred percent be okay with the deep state being a thing. Like, I’d be fine with them being right — the people who support Trump being like, “Oh, the deep state’s trying to bring him down!” Good. Good! Please succeed.

DANIEL: I wish conspiracy theories were real, because then we could find out who’s doing it, and stop them, you know.

BEN: We could cut the head off the hydra.

DANIEL: But the real problem is that reality is messy and uncertain and hard to understand, and lots of different actors are trying to achieve different goals that cut across our own. And everybody thinks that what they’re doing is good in some way. It’s just that no one is totally evil or totally wrong.

BEN: And some of them are bloody crisis actors, you know!

DANIEL: Mmm, exactly. So, these are terms that are used to prop up a right wing ideology in the face of contrary evidence. Crisis actors, false flag, deep state. Things that people rely on to make sense of their world.

KYLIE: I would like to finish off with one fantastic debunking by one of the students, Casky, who during an interview with CNN’s Wolf Blitzer, when asked, “Well, what would you say to the conspiracy theorists who think you are just a crisis actor?” he said, “Well, if you’d seen me in our school’s production of Fiddler on the Roof, you would know that nobody would ever pay me to act in anything.”

BEN: Zing! Zing zing zing zing zing! Although it’s like, having that good a line ready for that moment disproves — like, it works against him almost!

DANIEL: He would say that, wouldn’t he?

BEN: Yeah, he would. Crisis actor…!

DANIEL: Hey, let’s listen to a track, and this one is iTAL tEK with ‘Challenger Deep’ on RTRFM 92.1.

[MUSIC]

DANIEL: Lots and lots of great responses. Let’s hear them. Aaron sends an email. “It’s the new promotional age! Exacerbate your tedious. Seemingly the popularization of a grammatical dead ends?” Good point.

Garth sent me an email, studio@rtrfm.com.au “This seems to be a common issue for me in my favorite discipline of motor sport rallying slogans. Like, ‘I love rally’ — used by the promoters of the World Rally Championship no less — shit me to tears. To me, you enter a rally to go rallying because you are a rallyist.” Garth is insisting on the morphology. I think that’s really interesting.

“‘That’s rallying’ is a timeless quote and used to justify about any misfortune experienced in or around an event. But some people are starting to say ‘That’s rally.’ What is wrong with the world?” All right, well, remember, this is English we’re talking about so it’s not such a problem. This has been going on for thousands of years.

Steele says, “One year, the Christmas time marketing slogan for Starbucks where I work was ‘Let’s merry.’ It’s Christmas time. Merry, right? “If I didn’t want to get fired, I would have called corporate and be like, ‘Can you fire the entire marketing department? kthxbai.’ The marketing department is useless because they didn’t make a drink called the covfefe.” He continues: “It’s not the word class changing that I object to.” That’s good, because if you had, you would have been in trouble when you said that you want to ‘fire’ people. “I just object to it sounding stupid.” And I think that is actually a legitimate complaint. People think that if it sounds vacuous or if it sounds put on, they mind that a lot more than they actually mind the shifting of lexical categories, so that’s interesting.

Mike gives me a poser. He says, “Try expressing ‘He was born in 1987’ in active voice.” Okay, well, it’s got the ‘was’ and it’s got the past participle ‘born’. But what is the main form? Would you believe ‘to bear’? So I guess, if we add that participant back in, “He was born in 1987” becomes “His mother bore him in 1987.” Which is — you can see why that would be passive voice, right? because the person who — I mean, I know mothers are an important, right? Come on — but the person who was born really is the subject of the sentence, and so I can see why passive voice sounds a lot better. So Mike is making a fantastic point.

John on Facebook says “The only rule that matters in English is English will do what it wants when it wants with no prior precedent making a difference. Case in point: Arkansas English giving no f’s about Kansas.” I remember as a kid saying Are-Kansas and being corrected. Why? Why is it a ‘saw’? Silent s. Weird thing.

Matt chimes in: “Rules I would like to happily be rid of.” Nice infinitive split, Matt. I appreciate what you’re doing. Love your work.

Simon wanted to know if I could comment on this sentence: “Colourless green ideas sleep furiously.” Ah, yes. A very famous sentence by… Trotsky. Leon Trotsky, who was a secret linguist but also a secret environmentalist who had lots of green ideas but they weren’t very exciting, so they were kind of colourless. Nobody liked them. Those ideas would have to wait for many more years, during which time they would sleep. But they would arrive with a vengeance, so I guess these colourless green ideas must have been sleeping furiously. Good old Leon Trotsky. Let’s take a moment and remember his linguistic achievements.

That’s all for today’s episode of Talk the Talk. I’d like to thank you for listening. Thanks to Matt for taking us Out to Lunch very shortly, and I would also like to exhort you to check out our Facebook page, and we’re doing great stuff on Patreon.

Thanks for listening, and until next time, keep talking.

[OUTRO]

BEN: This has been an RTRFM podcast. RTRFM is an independent community radio station that relies on listeners for financial support. You can subscribe online at rtrfm.com.au/subscribe.

KYLIE: Our theme song is by Ah Trees, and you can check out their music on ahtrees.com, and everywhere good music is sold.

DANIEL: We’re on Twitter @talkrtr, send us an email: talkthetalk@rtrfm.com.au, and if you’d like to get lots of extra linguistic goodies, then like us on Facebook or check out our Patreon page. You can always find out whatever we’re up to by heading to talkthetalkpodcast.com

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

1 March 2018 at 5:43 am

Great episode! Your discussion of slogans made me think of my old university’s new one, “Here is How.” Not a fan!

2 March 2018 at 2:14 pm

Wonder why it’s always universities. Trying to escape a stodgy image? Not sure.