What do you call your family members? No, not like that.

We’re talking about kinship terms. How does your language handle family relations? Do you call your grandmothers on your mom and dad’s side the same thing? What’s a second cousin, and what’s ‘removed’?

We’ll find out on this episode of Talk the Talk.

Listen to this episode

You can listen to all the episodes of Talk the Talk by pasting this URL into your podlistener.

http://danielmidgley.com/talkthetalk/talk_classic.xmlPromo

Cutting Room Floor

Goons? The Goon Show? Goonies? Goon of Fortune? THERE ARE TOO MANY THINGS NAMED GOON. And there’s one too many books about emoji.

Randall Munroe v Elon Musk: Who would win? Do you have a franka? And why does children pluralise like that?

Also, Hedvig explains the nanny state. And Kylie is officially Ben’s groan-sister. Wait — groan-sister, or grown-sister? Is there a difference in pronunciation?

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/21246070

Animation

Patreon supporters

We’re very grateful for the support from our burgeoning community of patrons, including

- Jerry

- Nicki

- Termy

- Ann

- Helen

- Jack

- Matt

- Sabrina

You’re helping us to keep the talk happening!

We’re Because Language now, and you can become a Patreon supporter!

Depending on your level, you can get bonus episodes, mailouts, shoutouts, come to live episodes, and of course have membership in our Discord community.

Show notes

Philly students create slang glossary for teachers

http://www.phillytrib.com/news/philly-students-create-slang-glossary-for-teachers/article_d4ea1f4a-5260-532d-9a7a-0ee268423611.html

Philly Students Create Slang Glossary To Keep Teachers In The Ebonics Loop

https://blavity.com/philly-students-create-slang-glossary-to-keep-teachers-in-the-ebonics-loop

Wiktionary: bogart

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/bogart

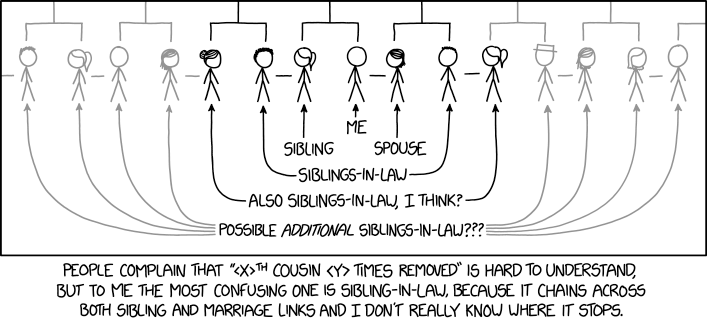

XKCD: Sibling-in-Law

https://www.xkcd.com/2040/

Relationship chart

Etymonline: nephew

https://www.etymonline.com/word/nepotism

Etymonline: step

https://www.etymonline.com/word/step-

Systematic Kinship Terminologies

http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/arts/anthropology/tutor/kinterms/termsys.html

The Very Complicated Chinese Family Tree

http://blog.tutorming.com/mandarin-chinese-learning-tips/family-tree-relatives-in-chinese

Family words in Chinese languages

https://www.omniglot.com/language/kinship/chinese.htm

Steve Bannon blasts Elon Musk: He’s an immature man-child

https://money.cnn.com/2018/08/30/media/steve-bannon-elon-musk/index.html

‘Best PR I’ve had in a while’: Elon Musk celebrates that Steve Bannon called him ‘an immature man child’

https://www.businessinsider.com.au/elon-musk-steve-bannon-immature-man-child-2018-8

10 Interesting Facts About the Etymology of Au Pair

http://www.aupair.org/blog/10-interesting-facts-about-the-etymology-of-au-pair/

Peter Dutton caught up in new au pair controversy

https://thewest.com.au/politics/federal-politics/peter-dutton-caught-up-in-new-au-pair-controversy-ng-b88945888z

‘Winning the lottery’: Australian ministers waved through dozens of visitor visas

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/sep/02/australian-ministers-waved-through-34-visitor-visas-since-2012

Peter Dutton au pair decision helped former Queensland Police colleague

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/peter-dutton-au-pair-decision-helped-former-queensland-police-colleague-20180830-p500t3.html

‘Nanny state’: Bill Shorten pokes fun at Peter Dutton over au pair controversy

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/sep/01/nanny-state-bill-shorten-pokes-fun-at-peter-dutton-over-au-pair-controversy

Tired: big data

— Paul Musgrave (@profmusgrave) 30 August 2018

Wired: massive data

Inspired: small-batch, artisanal data

Urban Dictionary: shitpost

https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=shitpost

Etymonline: organ

https://www.etymonline.com/word/organ#etymonline_v_7139

Etymonline: mean

https://www.etymonline.com/word/mean

Transcript

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]

[INTRO]

DANIEL: The following is an RTRFM podcast. RTRFM is a community organisation, and relies on volunteer and listener support. To learn more about what we do, visit rtrfm.com.au.

[THEME MUSIC]

DANIEL: Hello and welcome to this episode of Talk the Talk, RTRFM’s weekly show about linguistics, the science of language. For the next hour, we’re going to be bringing you language news, language terminology, and some great music. Maybe we’ll even hear from you. My name is Daniel Midgley. I’m here with Ben Ainslie.

BEN: Good morning.

DANIEL: And Hedvig Skirgård.

HEDVIG: Hey.

DANIEL: What do you call your family members? No, I don’t mean like that. We’re talking about kinship terms. How does your language handle family relations? What’s a second cousin, and what’s “removed”? We’re going to find out on this episode of Talk the Talk.

BEN: So, I don’t know about you guys, but I call my family UGH.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: A lot of us do.

HEDVIG: I find English terminology a bit confusing, I must admit. The whole removed thing is mysterious to me.

DANIEL: Aha.

HEDVIG: I think I know what it is, but I’d love to confirm that I know what it is.

DANIEL: Okay, well, we’ll get to that. But first…

BEN: What’s going on in the world of linguistics in the week gone past?

DANIEL: I noticed this great article from Sarah Hoover from the Philadelphia Tribune, and also Ashley Atwell in blavity.com. Check this out. A couple of high school students in Philadelphia have developed a glossary of slang to help their teachers.

BEN: YES.

HEDVIG: This seems traitorous to other students.

BEN: I was actually going to say, this is a, just a tremendous olive branch being offered by the youth of today.

HEDVIG: Is it though? Or is it, is it something mean baked into this? Are they going to teach them the wrong words?

BEN: Ah, wow. You really don’t trust teenagers!

HEDVIG: No! There are reasons why they create secret languages, because they don’t want adults to understand, right? This is suspicious.

DANIEL: This kind of thing can backfire. A friend of mine told me about how a group circulated a lot of drug slang among the parents, so that parents would know if their kids were talking about drugs. And the kids got a hold of the guide and just started using the terms for non-drug slang, thereby emptying it of meaning.

BEN: YES.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: Like, this is when the term BOGARTING A JOINT was new. And so they started saying: Hey, don’t bogart my sandwich! And it… which I think everybody says now.

BEN: Yeah, I definitely say that about all measure of things.

HEDVIG: I don’t say that about anything. What? Sorry. Um… what is that??

DANIEL: Well!

BEN: I believe it’s from the fact that Humphrey Bogart would, like, steal scenes. To bogart the joint is to sort of like hold the marijuana cigarette for too long.

DANIEL: I thought that it was that he would take big, long drags on cigarettes.

BEN: Aaaaaah.

HEDVIG: Is it like hogging?

BEN: Yes, yes.

HEDVIG: Oh, right, okay.

DANIEL: This is fun! I’ve known about this slang for 30 years and now I’m introducing it to Hedvig.

BEN: Yes, thank you. No, in Swedish we just, we have a loan word, HOG, from English. Yeah.

DANIEL: Yeah.

BEN: I like it.

DANIEL: This guide was written by two students, Horace Ryans III and Khalid Abogourin. They did it so that they could help first year teachers get used to Philadelphia slang, which we all know is kind of its own thing. How well do you know Philadelphia slang?

BEN: [SPUTTERS] Oh, mate! I’m so glad you’ve come to me because — whooooo! Me and Philly, we go way back. Not really at all. I know nothing.

DANIEL: Well, we’ve talked about JAWN on the show.

BEN: As either a man who buys prostitutes or the toilet?

DANIEL: Nope, neither one. That’s a JOHN. But this is a JAWN.

HEDVIG: Oh!

DANIEL: So a JAWN is just a thing. Hey, hand me that JAWN over there.

HEDVIG: Ohhhh, okay.

DANIEL: And it could be anything.

HEDVIG: That’s actually a Scandi word: JOON. I think, I think DOON. Yeah. Okay.

DANIEL: What, why, what does it mean?

HEDVIG: No, just THINGAMAJIG.

DANIEL: Really??

HEDVIG: DOON does, at least. I think JOON is, I think — actually now that I think about it — I think JOON means a stupid person.

DANIEL: Oh, okay.

HEDVIG: A poor… poor person or a stupid person.

DANIEL: How about this one? If someone is DRAWLIN’… aw, man…

BEN: Drawlin’?

DANIEL: That student was drawlin’ in my class today.

BEN: Nuh.

DANIEL: Take a guess.

HEDVIG: Um… were they secretly trying to hide a yawn?

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: I… the only thing I can do is the dumb thing and use logic. And I was like, well, to drawl is to sort of speak lazily. So maybe they were speaking poorly of someone, or something like that?

DANIEL: Okay. It actually means to act out. In class, say.

BEN: See, that makes no sense at all.

DANIEL: Or OCKY. Aw, I paid a lot of money for it, but turned out to be ocky.

HEDVIG: Fake?

DANIEL: Yep, it’s fake.

BEN: Right.

HEDVIG: Yayyy.

DANIEL: Now, I love this story for so many reasons. First reason is that you’ve got students preserving the local language and documenting it, which is so great.

BEN: Yeah, it’s almost like a group of Cockney students, like, helping out people who speak the Queen’s.

DANIEL: Yeah, it’s also students thinking and reflecting about their own language use. One thing that I noticed was it had to fit on one page. So they had to cull and get only the most important terms, like the most, what they thought were the most frequent terms. That’s fantastic.

HEDVIG: Mhm.

BEN: I like that.

DANIEL: But also, it’s telling teachers: you could benefit from understanding us better and that’s so good because we need to keep remembering that the teacher is a learner and that communication is a two-way street.

HEDVIG: Yeah, yeah, I’m still suspicious. [LAUGHTER] I just… just as we were talking about this… the funny thing is… I have a funny story, sit back. The funny thing is that me, Hedvig, have actually… in Sweden there was a similar thing where the Institute for Public Health had made a little book, like a handy guide for parents about teenagers and habits and words. And the back of it, they had little word list. And it was really outdated and had a lot of errors in it. So I wrote to the editor and just said: Just FYI, no one says this thing, and this thing actually means that thing, and like… And they were like: Oh, can you proofread for our next edition? So I’m actually credited as, like, the editor of the word list. So I’ve actually made this and I’m STILL distrustful, even though I didn’t lie. So that’s… I don’t know what that says about me.

BEN: Yeah, that’s, that’s what I’m w… like, are you just externalising your own regret over not being terrible?

HEDVIG: I think it’s that… you know that meme…? The meme template that is floating around with…

DANIEL: A lot of conversations with Hedvig start this way, by the way. [LAUGHTER]

BEN: Oh, what a great supercut, Daniel. “You know this meme? You know this meme? You know this meme? You know this meme? You know this meme?”

HEDVIG: I love memes! But there’s a meme template, you’ve seen it, which is like, Is your teenagers sexting? Here are some known abbreviations that you should know about.

DANIEL: YES I remember this.

BEN: Yeah yeah yeah

HEDVIG: And then it’s like bullshit things. And sometimes there are linguistic themed ones, so that — like, I don’t know, BRB means Bring Back Basque instead of Be Right Back or something.

DANIEL and BEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

HEDVIG: You know, it’s just really nutty. So I think I’ve seen a lot of those, which makes me… I think that’s what’s influencing me.

DANIEL: Mm, possibly.

BEN: You do realise that not all people shitpost, right?

HEDVIG: Really??

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: First of all…

BEN: I like that this is, like, genuinely revelatory, to such a degree that, like, you don’t believe? You’re just like: No! Fuck! That’s wrong.

HEDVIG: Wait, does everyone know what shitpost is?

DANIEL: Yes, all of our listeners know what shitposting is.

BEN: Yes, I agree.

HEDVIG: Okay, cool, cool, cool, cool, cool. Just checking. Oh, I hope the editors of that book is not listening to this and second guessing my edits. Yeah.

BEN: Well, no, the point is if the editor of the book was listening to this, he’s, he’s now — or she — is very convinced that they got it right! Because you’re just like: ~Oh, yeah, no, like, most teenagers would lie and I suspect all teenagers now lie. But I didn’t lie.~

DANIEL: As far as language goes, teachers feel a responsibility to teach Standard English. But that can happen lots of different ways and a really effective way to do that is to recognise the validity of other ways of speaking, and meeting students on their own linguistic turf is a good way of communicating respect and affirming the validity of all forms of language. So good on these students. Good on the teachers for responding well. Everybody wins.

BEN: Well, with that little teenage tidbit firmly lodged in your craniums, why don’t we take a track, Daniel?

DANIEL: Okay. Let’s do “Don’t Bogart My Heart” by Darren Hanlon on RTRFM 92.1.

[MUSIC STARTS]

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS] Is that an actual song?

DANIEL: Yes, it is!

HEDVIG: NO! Oh my god.

[MUSIC BREAK]

BEN: If you are just tuning in to Talk the Talk, this week we are delving into the rich varied world of kinship terms. What do you call your second cousin twice removed? Is that your cuz? Or is that Steve, that guy who just never really made sense? That’s what we’re talking about on this episode of Talk the Talk.

HEDVIG: Also, why was anyone removed at any point? I don’t, I can’t… can you English speakers explain this removed thing? I’m terriby…

DANIEL: Yes, I can.

HEDVIG: Thank you.

DANIEL: Now Ben, you’re going to love this because this episode was inspired by an XKCD cartoon.

BEN: [ANGELIC CHOIR NOTE]

DANIEL: You can even go there right now. It’s still up as of this recording.

BEN: Randall Munroe is the Elon Musk the world actually needs. [LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: So this cartoon has a row of people connected by marriage and/or sibling relations.

HEDVIG: And/or?? Is anyone connected by both?? [LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: No! Not on this chart. It’s definitely acyclic.

HEDVIG: Okay. All right. Cool.

BEN: If it’s literally any royal lineage tree, than yes.

DANIEL: The caption says: People complain that xth cousin, y times removed is hard to understand, but to me the most confusing one is sibling-in-law because it chains across both sibling AND marriage links, and I don’t really know where it stops. So you’re married to someone and their — I don’t know — brother is your brother-in-law, but then they’re married to someone. Is that your sister-in-law? What if she has a sister? Is that person still your sister-in-law. It just goes and goes and goes.

HEDVIG: I saw the comic, and I thought it was very funny, but I also thought that it just stopped at one degree. Doesn’t it?

DANIEL: Well, the lexicon doesn’t make it clear.

HEDVIG: Oh.

BEN: I guess for me, it’s a bit of a nonstarter because we have, for the most part, deeply individualist families. Right? Like, I think the reason there’s not words for the sister of the woman my brother-in-law is married to is because I don’t care who that is.

DANIEL: Yeah. I know that my sister has a husband and that he’s got a sister, but I don’t think of her as a sister-in-law because I never think about her at all.

BEN: Right. I think of her as Deb’s sister. Right? Like, if I ever have to.

DANIEL: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Or just their name, right?

BEN: Yeah,

DANIEL: But I will admit that it’s a tricky concept, especially in English. Let’s talk about English terms of address here.

HEDVIG: Is this when I’m going to learn about removed? Yayyyy

DANIEL: Are you ready to do it?

HEDVIG: Yeah!

DANIEL: Okay, Ben, you wanted to get in on this.

BEN: I wanted to guess. So I remember 2nd 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th cousins are all to do with the distance back that the link goes familiarly.

DANIEL: Yeah. You pretty much got it there. So here’s what you have to imagine. You have to imagine a pyramid with lots of levels like bricks, right?

BEN: Yep.

HEDVIG: Okay.

DANIEL: Now, at the top of the pyramid is a common progenitor. That’s the ancestor in common for the two people whose relationship you want to know. So…

BEN: In my case, King George the Fourth.

DANIEL: What??

HEDVIG: Charlemagne.

BEN: Nice one.

DANIEL: Oh, everybody says Charlemagne. Let’s take a slightly less remote example. Let’s take me and my sister. All right?

BEN: Okay.

DANIEL: The common progenitor is my mom or my dad…

BEN: Yep.

HEDVIG: Mhm.

DANIEL: And my sister and I are one level down on this pyramid. So I’m going to slide one level down the right side of the pyramid. That’s me. And my sister is going to slide down one level on the left.

BEN: Cool.

HEDVIG: Mhm.

DANIEL: Okay.

BEN: So let’s call this tier 2. We’re now on tier 2.

DANIEL: We’re now on tier 2, that’s the sibling relationship. Now we’re going to go another level down on my side and hers. Now we’re talking about my child and her child and they are, of course, in English…

ALL: Cousins!

DANIEL: Easy enough so far. But now what happens if we both go down one more level to her grandchild and my grandchild? I don’t have any yet, but let’s say I do. Then they will be…

HEDVIG: Second cousins.

DANIEL: Yeah, that’s right. They’re second cousins to each other. And one level even further down will be third cousins and so on and so on and so forth. But if we don’t slide equally down on both levels, like if it’s… if it’s my grandchild and her grandchild, that’s easy: second cousins. But let’s say we stop at my grandchild, but on her side we go down one more level. Those two wouldn’t be second cousins. They’d be second cousins…

BEN: Once removed.

DANIEL: Removed by one generation.

HEDVIG: And they can’t be like great uncles or great nephews?

DANIEL: Great uncles and great nephews are terms that we only use when you’re one level down on the pyramid on one side, and then the other side you could be wherever you want.

HEDVIG: Ahh.

DANIEL: But if anyone is more than teo levels down, then you have to rely on this very strange third cousins, five times removed and so on.

BEN: Like, realistically, Daniel, when was the last time you really heard this being used to great effect in actual conversation?

DANIEL: In actual conversation, I heard it a lot when I was living in Utah and working at the Genealogy Library at BYU.

HEDVIG: [LAUGHS] Yes, right.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: And people would be in there all the time, talking about their relationships. And there was a chart like the one I’m describing, this pyramid chart on the wall. And you would have to know your stuff. Hey, I found out something interesting about the word NEPHEW.

BEN: Yarp?

DANIEL: I really love etymologies when they are so bleeding obvious in retrospect. But did you know that NEPHEW and NEPOTISM are related?

BEN: I did not.

HEDVIG: Yes.

DANIEL: You did know that?

HEDVIG: I took Latin in school.

BEN: Oh god, you’re so European.

HEDVIG: I know. Yeah. Went on a field trip to Rome.

DANIEL: Yep. This… it actually does come from Italian NEPOTE, which is nephew. And etymonline says: Originally the practice of granting privileges to a pope’s nephew, which was a euphemism for his natural son. Lovely, eh?

HEDVIG: Yeah, because people would have natural sons, and then get someone else to bring them up or adopt or things, right? A lot. That was really common practice. Or if, like, there was a young man that you really liked and you wanted him to inherit your house and your wealth, you’d just adopt him.

BEN: Sweet!

DANIEL: Nice.

BEN: Man, I need to get in a time machine and just look conspicuously heritable near some rich old people!

DANIEL: You can’t, Ben. You’d kill them all with some terrible disease.

BEN: Ah, that’s true. No, they’d kill me with some terrible disease.

HEDVIG: So actually for this segment, I looked up some more things about Latin. So my friend and fellow PhD student at ANU, Kyla Quinn, is working on kinship systems and comparing them across many languages.

BEN: Cool.

HEDVIG: And I asked her to send in some fun examples for our show.

BEN: Yes. YES.

HEDVIG: So she sent in four languages and she sent me the the kinship systems, and I sort of tried to work out how they worked. But I actually learnt one thing that’s a bit maybe crude but it’s funny. But the Latin term for paternal or maternal grandmother. It’s actually ANUS.

DANIEL: Oh, nice.

BEN: Oh, yes.

HEDVIG: Number one. Which also sounds a bit similar to YEAR. So they, they’ve got to be related. But the other thing I learned is they don’t have a difference… that the Latin kinship system, if I understand it… there wasn’t actually a difference between NIECE and NEPHEW. So what the gender was of the person you’re related to didn’t matter. It was the same word.

BEN: Can I say as well that that actually makes a lot more sense than NIECE and NEPHEW, because I have a friend who recently… her sister had more… another kid. Right? So until recently she had two children, like 5 and 7, both girls. Right? So it was always like, I’m going to see the girls or i’m going to see my nieces. Now that they’ve had a son, it actually becomes quite difficult. “I’m going to see my nieces and nephews.” Or “I am going to see the… girls and boys.” Like, it doesn’t actually work. Like, you can say, “I’m going to see the kids,” but that’s so general that you could mean a number of different things. So in English, NIECES and NEPHEWS actually gets a bit unwieldy, I find.

DANIEL: We can have them be NIBLINGS.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Near siblings. I love it!

DANIEL: A real neologism that’s been suggested.

HEDVIG: That’s great! I love it.

DANIEL: Niblings.

HEDVIG: So the cool thing is that the Latin… it doesn’t matter if they’re a niece or nephew, but it matters whether you have them through your sister or through your brother.

DANIEL and BEN: Ah.

HEDVIG: So it’s FRATRUELIS if it’s via your brother, and it’s SOBRINUS if it’s via your sister.

DANIEL: Right. Now there are six different classification systems, according to anthropologist Louis Henry Morgan, who did this work in the 1800s. And not everyone uses the system anymore, but you do see references to it. So he proposed 6 basic systems, and Latin follows the Sudanese kinship system. That’s the most detailed. For this system, everybody on your mom and your dad’s side gets a different term — except for in Latin; the exception is nieces and nephews. Hey, I like latin, but there are tons of other languages. Could we take a break and then come back and talk about them some more?

BEN: First of all, we need to sort out: what do you mean there’s tons of other languages?

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: There are other language besides Latin and English.

BEN: Have you guys been holding out on me about something? [LAUGHTER] All right. Well, now that that mind blow has been dropped, yeah, let’s take a track, and on the other side of it, we’re gonna find more kinship terms for lots of different languages. But hey, if you’ve got questions and/or feedback and/or want to make fun of Daniel, you should get in touch. You can get hold of him on the telephone: 9260 9210.

DANIEL: You can make fun of me by email, that’s talkthetalk@rtrfm.com.au.

HEDVIG: And you can also find us on all the social medias. Just search “talk the talk” or talkpod. We’re on Facebook, we’re on Twitter, and Instagram.

DANIEL: But now let’s listen to Moana with Cloud Mother on RTRFM. Stay tuned; more talk after this.

[MUSIC BREAK]

BEN: We’re talkin’ family. All about that fami-LEE on Talk the Talk this week. There are so many different ways to refer to your family, other than UGGGGHHHHHH.

HEDVIG: So, as Ben was saying before the break, there are actually lots of other languages out there that are not Latin or English. I know; it’s amazing.

BEN: WHAT

DANIEL: Tons.

HEDVIG: And they’re not even related to them, as far as we know.

DANIEL: Yeah, we already saw the Sudanese system, where everybody gets a different term all across the family tree — mother’s side, father’s side, all different. But there are others.

HEDVIG: So I asked my friend Kyla Quinn who’s a PhD student at ANU and works on kinship systems in lots of different languages to send over some fun examples. So she is the one who provided me with the sheet for how Latin works.

DANIEL: Thanks, Kyla.

HEDVIG: I actually never learned this, even as I was taking Latin classes. There’s a thing about siblings in a lot of different kinship systems where you place a lot of importance whether it is the same sex or not, right? So if I’m a girl, and I have a sister — so we are both female.

BEN: Yes.

DANIEL: Mhm.

HEDVIG: So my… my sister Mina, for example — she’s my sister. My brother Hannas — he also calls Mina his sister, even though they have different gender. Right?

BEN: Okay, I get you. I get what you mean. Like, that’s in English. That’s normal. Yeah yeh yeah.

HEDVIG: Yeah that’s… that’s how a lot of languages work. But some languages say: No no no no no. You have a very different relationship to someone else, depending on if you have the same gender or not.

DANIEL: So I know for example in Māori, the word is TEINA. And if I say my teina, it means that it’s my male brother. But if my sister says my teina, then it means her sister.

HEDVIG: Exactly! So it’s the same in Samoan. This is USO. And in Kalau Lagau Ya, which is a Pama-Nyungen language from the North of Queensland, you actually have a different term. If you are cross-sex siblings, you are BABATS, and if you are same-sex siblings, you are TOKOYAB.

DANIEL: Cool.

HEDVIG: So the terms SISTER and BROTHER doesn’t really translate directly then. The thing about some of these relationships is also, if you have strong taboo, or things like, if you really want to highlight which relationships are meant to be able to be intimate and which ones are not, than this could matter. For cousins, for example, it makes sense… if you want to avoid cousin marriages, you want to know whether you are same or different sex.

DANIEL: The language that I’m thinking of in connection with this is Panyjima — an Australian Aboriginal language in the Pilbara region — because they have a really interesting system of moieties and they call it skins.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: Four groups that everybody belongs to, and which kind of determines who you should marry. So for…

BEN: Yes. The Noongar do this as well.

DANIEL: Yeah.

BEN: Yeah yeh yeah yeah yeah.

DANIEL: So for example, in Panyjima you’ve got Panaka, Karrimara, Milanka, and Purrungu. And if… let’s just say that I’m a Panaka man, I should marry a Karrimara woman, and then our kids will be Milanka. And the thing about the generations is that it will go Panaka and then my kids will be Milanka, and then their kids will be Panaka depending on sex and stuff like that. Really interesting set up. How else do other languages handle it?

HEDVIG: I’ve also got Marshallese here, where they make a big point out of younger and older. So YETU is a term for either a girl’s younger brother or younger sister, it doesn’t matter. You’re younger than me!

DANIEL: So anybody younger than you is just that.

BEN: Ah, so age is far more important than gender.

HEDVIG: Yeah. We’ve also got another Australian language, but this time non-Pama-Nyungen, so it’s Tangkic, where you do have… similar to Marshallese, you care about the older and younger, but you actually do also care about the gender. So you have female speakers, younger brother or older brother will be different and also the sister. But… so you sort of maximise, you do both sex and age.

DANIEL: I am just looking at the system used in Mandarin, and I’ve got to say: that is incredibly detailed. For this one, you’ve got you. You’ve got sister and brother. You’ve got a different word for your aunties and uncles on your mom’s side and your aunties and uncles on your dad’s side.

BEN: Just to be clear that means four different, unique words.

DANIEL: That’s right. But then you’ve also got separate words for maternal cousins, boys and girls…

HEDVIG: Oh, that’s good.

DANIEL: …maternal cross cousins, paternal cousins related to you and paternal cross cousins. So it’s…

HEDVIG: Wow. Yeah, that’s good.

BEN: Whoa. That is comprehensive.

HEDVIG: And they also have age with siblings, right?

DANIEL: Yeah. In Mandarin, the term for brother-in-law isn’t just brother-in-law. There are 16 different things that it could be. Could be an elder sister’s husband, the youngest sister’s husband, a husband’s elder brother…

BEN: Whoa.

HEDVIG: Wow, yeah.

DANIEL: …a husband’s younger brother, a wife’s elder brother, a wife’s younger brother. Then an elder sister’s husband, a younger sister’s husband. It just goes on and on and on.

HEDVIG: Wow. I like that.

BEN: That’s intense.

DANIEL: Yeah! It’s one of the most detailed classificatory systems that you can have.

HEDVIG: Like, it’s amazing the diversity you find in kinship systems, and it’s been a very low hanging fruit for anthropology and linguistics for a long time because it’s quite relatively easy data to collect and to compare. And part of the very interesting work that Kyla Quinn is doing at ANU is looking if there’s any way we can trace the language family relationship through the kinship organisation. So is it the case that kinship systems is something that’s very easily borrowed? For example, if you come in contact with a new language and they have a different kinship system, are you likely to take on their organisation of it? Or are you likely to stay sort of put with the one you have? And if you’re likely to stay put, that means that we can probably trace lineages… like, language lineages. The genealogy of languages, not the genealogy of speakers.

DANIEL: Well, this whole kinship thing is super fascinating, but I’d love to hear what our listeners have to say about it. For example, do you live in a language that has interesting — from an English speaking perspective — terms of address? Do you call your maternal grandparents and paternal grandparents the same thing? What’s in your linguistic bag of tricks?

BEN: Or… flip side, what do you find weird about English’s terms of address? Like, if you come from a different language tradition, and you’ve had to learn English’s ones — as Hedvig has — like, what did you look at and just go: Why? What are you calling them that for?

DANIEL: Hedvig, what do you think?

[25m]

HEDVIG: I think the cousins thing is weird, because [LAUGHS] well, both the whole removed thing — that’s just bonkers, but at least that’s not in use — but the whole second and third… because… so we have a… cousins are only first cousins in Swedish, and second cousin is an entirely different word. The other thing I really funny about English is that you have the same word for your maternal and paternal grandmother. And even though you have the same word, you also don’t seem to think that it is worthy of distinction. So people will say: Oh, I’m going to see my grandmother on the weekend. And I’m like: surely you have it too, and surely they are different people and it matters which one you’re seeing.

DANIEL: And then we say something like: Oh, on my mom’s side.\

BEN: Yeah.

HEDVIG: Or not at all. They’d just be like: I’m going to see my grandmother, or my grandmother passed away, or something and I’m like: Which one? Surely this matters, and people don’t seem to care. That surprises me.

DANIEL: Go ahead, Hedvig. Lay the words on me in Swedish. I want to hear it.

HEDVIG: Oh, well, paternal is FARMOR — father’s mother — and maternal is MORMOR — mother’s mother.

BEN: I just love that you are getting all high and mighty about the fact that we don’t name them, and then your system is just the most boring possible words! It’s Dad’s Mum and Mum’s Mum.

DANIEL: That’s my dad mom! That’s my mom dad!

HEDVIG: Yeah! That’s my dad mom. That’s my mom dad. Yeah! It’s great! You should all do it.

BEN: It’s just so bad. Like, no! I don’t want to do that. That’s a terrible idea. I don’t like your idea at all. Your language is a bad language.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: So this repeats throughout the whole system. [MORE LAUGHTER] So grandchildren is child child.

DANIEL: Yup.

BEN: Oh my god.

DANIEL: It’s modular, like furniture.

BEN: Oh yeah, this is the IKEA of kinship terms.

DANIEL: Oh my gosh.

HEDVIG: Yeah! So your paternal uncle is your father-brother, et cetera.

DANIEL: Of course he is!

HEDVIG: Like… yeah. And actually, you guys were saying before about niblings. So we can say sibling children.

DANIEL: Yup.

BEN: Oh wow.

HEDVIG: Yeah. I have two sibling… I have three sibling children.

DANIEL: I’m actually a little bit surprised. Like, the Swedes are normally a bit funner than Germans, but this is the most German thing I’ve ever heard. [GERMAN ACCENT] Zis is my father-mother, and zis is my father-mother-mother. And below her is my child-child and my child-child-brother-child.

HEDVIG: We love compounding! We love compounding. It’s the best thing! Actually, for mother-sister and father-sister, they have fused a bit. So they’re not FASH-SYSTER; they’re FASTER, so there’s a bit of fusing in one of them.

BEN: Yeah. Okay. Wow. That’s really constituting word-dom.

HEDVIG: It’s great, though, ’cause you can decide level of granularity. So for example, I can say that I have three sibling-children, or I can say that I have two brother-children. Or I can say that I have one brother-daughter.

BEN: Ahh.

DANIEL: Flexibility.

HEDVIG: So I can pick whichever level I feel like I think is relevant.

BEN: Look, I will freely concede, in true Scandi tradition, it is a clean design solution.

DANIEL: I’ll say.

BEN: But I don’t know if it’s necessarily going to win any, like, aesthetic awards.

HEDVIG: So one thing I want to hear from the listeners, actually, is how to deal with novel kinship situations. Like, if you marry someone who already has kids. What are they to you?

BEN: Oh, stepchildren. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

HEDVIG: So we call them bonus-children.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Bonus-children! Nice!

BEN: Bonus-children! I love it.

HEDVIG: Yeah!

BEN: Yeah. That, I am way more on board with.

HEDVIG: When I was little, the term was actually plastic children.

DANIEL: Wow.

BEN: WHAT

HEDVIG: And plastic dad.

BEN: Why…?

HEDVIG: So if my mother re-married, her new partner would be my plastic dad. But now people… I think people have started saying bonus-dad for that.

BEN: I love bonus.

DANIEL: That’s cool. Well, that’s much better than STEP in English, which comes from Old English STEOP, which has connotations of loss. It comes from a word meaning BEREFT.

BEN: Wow. That’s sad.

DANIEL: Well, it came from a time when orphans were common, but now we don’t really do orphan so much. We tend to, you know, have re marriages. But the step has remained.

BEN: There you go! Well, I think we had better book it to a track, and then on the other side of that, you know… a thing. A certain segment that people might enjoy, or not. I don’t know.

DANIEL: Well, let’s listen to Foam with “Eat Your Family” on RTRFM 92.1.

[MUSIC BREAK]

BEN: Hedvig, I would like to think that you’re, my honorary internet-sister.

HEDVIG: [EXTREMELY FLATTERED] Oh my gosh.

DANIEL: Would that be a thing that works in English?

HEDVIG: Yes! I accept!

BEN: And then Daniel, you’re my… you’re my nerd father.

DANIEL: Okay.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: But Word of the Week is absolutely my hate-segment. [LAUGHTER] I just applied Swedish kinship terminology to all of the things involved in this show.

HEDVIG: Loving it.

DANIEL: Our first Word of the Week is MAN-CHILD.

[LAUGHTER]

HEDVIG: Yep.

BEN: How is this a Word of the Week? This has been around for ages.

DANIEL: Well, it’s come into prominence because Steve Bannon, who is a Nazi, former Trump strategist and worker at Breitbart… By the way, he wasn’t the only Nazi at the White House. He wasn’t even the only Nazi named Steve at the White House.

HEDVIG: Oh, god.

DANIEL: But having been kicked out of the White House, he’s now taken his malodorous machinations to Europe, where he can do some real damage. There have been Nazi rallies in Germany lately. Coincidence?

BEN: Ugh.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: Anyway, Steve Bannon the Nazi went after who else but Elon Musk.

BEN: Wait. Have we got two man-babies fighting each other?

DANIEL: We might!

BEN: Is there a toddler fight? Is that what’s going on here?

DANIEL: Could be. He went after him in an interview about taking Tesla private, and then suddenly not. Full disclosure: I do own Tesla stock. Steve Bannon said: “He then has an emotional breakdown with the New York Times. This is the level of maturity you have with these people. They are all man-childs.”

HEDVIG: Ooo.

BEN: Who’s THEY? What’s the THEY he’s referring to?

DANIEL: I think he means CEOs with a lot of power.

BEN: Oh. Okay.

HEDVIG: I love it when a new compound word gets a weak conjugation.

DANIEL: Can you explain?

HEDVIG: When you compound something like MAN-CHILD, the separate bits have their own conjugation, like MEN and CHILDREN.

DANIEL: Right.

HEDVIG: And it just so happens that MAN and MEN is not a regular way of forming a plural. The way that English usually does it is by adding an -S.

DANIEL: MANS.

HEDVIG: So: GIRL, GIRLS. BOY, BOYS. CHAIR, CHAIRS, et cetera. But some words behave a bit funny. So we have GOOSE and GEESE, and MOOSE and…

BEN: MOOSES.

DANIEL: MOOSE.

HEDVIG: MEESE? Surely. C’mon.

[LAUGHTER]

DANIEL: Sorry.

BEN: No, it’s not MEESE. It’s definitely not MEESE.

HEDVIG: We have to make MEESE happen. We have to.

BEN: It’s not MEESE. It’s not a thing.

DANIEL: Stop trying to make MEESE happen! It’s not going to happen.

BEN: We have SHEEP and SHEEP.

HEDVIG: It is happening. [LAUGHTER] Yeah, we have lots of these, right? And it just so happens that both MAN and CHILD are both irregular plurals. So we have CHILD and CHILDREN, and we have MAN and MEN. And sometimes when you combine things, it’s as if speakers go: well, if it’s combined it’s a new thing. And if it’s a long thing, long things have a higher tendency to be regularly pluralised. Have you noticed?

BEN: MAN-CHILDS.

HEDVIG: Yeah. So then you suddenly get MAN-CHILDS. I love it.

BEN: Instead of MEN-CHILDREN!

DANIEL: MEN-CHILDS…

HEDVIG: Or, yeah… MEN-CHILDREN or MAN-CHILDREN.

DANIEL: You could have MAN-CHILDREN, you could have MEN-CHILDREN, you could have MAN-CHILDS and you could have MEN-CHILDS. What do you like?

HEDVIG: I like MAN-CHILDS.

BEN: I like MAN-CHILDREN.

HEDVIG: Why.

DANIEL: I like MAN-CHILDREN too. So I took a look in the Google Ngram viewer. Guess which one it said was the most common.

BEN: MAN-CHILDS.

DANIEL: No.

BEN: Ah!

HEDVIG: MEN-CHILDREN.

DANIEL: It said MEN-CHILDREN was number one.

BEN: Nooo

DANIEL: And MAN-CHILDREN was a distant number two. Also, Graham Starr @GrahamStarr of New York Magazine tweeted to @MerriamWebster: Hi, dictionary! Important question: is the plural of manchild “menchild” or “manchildren”? And the dictionary replied: Men-children. M-E-N.

BEN: Wow.

HEDVIG: So they just went with the most frequent.

DANIEL: Yeah, I think so. I think they must have.

HEDVIG: Yep.

DANIEL: That’s very surprising to me because when we form compounds, we usually just throw their morphology out the window and just compound it and add -S. Like LEADFOOT, right? A driver who speeds? What would you say? “All those speeding drivers! They’re all a bunch of…”?

BEN: LEADFOOTS.

DANIEL: LEADFOOTS.

HEDVIG: I’m learning so many new words. I now know what LEADFOOT is.

BEN: Not LEADFEET.

DANIEL: Nobody says LEADFEET. You compound first, and then you add -S. And if it’s irregular, don’t worry about it.

HEDVIG: Exactly! Yeah!

DANIEL: So you’d think that people would pluralise this like Steve the Nazi. But they don’t. They say MEN-CHILDREN. And I don’t know why.

BEN: That’s interesting.

HEDVIG: Maybe ’cause CHILD/CHILDREN is so… like, you use it so often, it’s so present in people’s minds they can’t really… Yeah, well people talk about feet a lot, as well. Okay, scrap my idea.

BEN: You’re thinking, like, mental muscle memory basically.

HEDVIG: Yeah.

DANIEL: No, but I get that, but then that would explain MAN-CHILDREN, but it wouldn’t explain MEN-CHILDREN — pluralising them both, unless people just said: I’ve gone this far throwing the rules out the window. I’m going to pluralise MEN as well. Aaah!

BEN: All the plurals!

DANIEL: Feels good. Meanwhile @languagejones had a poll, 147 people responded and said that: 62 percent thought MAN-CHILDREN was the best answer. So I don’t know. Our next Word of the Week comes from Tim Wilson, the MP.

BEN: Uh-oh.

DANIEL: He’s a member for Goldstein in Melbourne. Do you know this guy?

BEN: No, but I’m just worried because politicians are uniformly terrible.

HEDVIG: Yeah, me too.

DANIEL: He tweeted — he accidentally a word — “To those of you who […] why I’m so hardline against the #nannystate, it’s quite simple. I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees.”

BEN and HEDVIG: Oh my god.

BEN: Oh, mate.

HEDVIG: It’s sounds American!

DANIEL: We’ve got a real bad ass over here. I can totally picture him writing that tweet and maybe knocking back a Mountain Dew or something. So Lia on Twitter responds, with what I think is just the perfect response. “Your government is really more of an AU PAIR STATE than a nanny state.”

BEN: BOOM. [LAUGHTER] Oh SHIT.

DANIEL: Isn’t that just devastating?

BEN: That’s brutal.

DANIEL: That might not make sense to people who aren’t following the current Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton controversy.

HEDVIG: Oh, my god, I… yeah. I can’t wait to go back to Australia and try and understand this.

DANIEL: Okay, well, let me see if I can explain it. So he thinks it’s okay to leave people of colour to rot in offshore prisons.

HEDVIG: Mhm.

BEN: Literally to starve themselves to death. Like, that’s actually happening right now.

DANIEL: Scott Morrison’s project by the way. But if a French or an Italian woman is at risk of deportation, it’s time to spring into action.

HEDVIG: Oh, yeah.

DANIEL: Seems that there were a couple of au pairs, one from France, one from Italy. They were going to be deported, but Mr Dutton intervened to save them from deportation, and it seems that they went to work at homes of Peter Dutton’s friends.

HEDVIG: Oh, did they now? Well, well.

DANIEL: One was a former Queensland police colleague and another one was connected to an AFL boss. The tweet goes on, Lia’s tweet. She says: Your government is really more of an au pair state than a nanny state. The au pair state is a small government, only interested in working for a small circle of moneyed interests, and having an even smaller circle of empathy and integrity.

BEN: Boom. Wow.

HEDVIG: Wow.

BEN: That’s brutal.

DANIEL: Mm.

BEN: I don’t understand the difference between an au pair and a nanny. Is it just a rich person’s nanny?

HEDVIG: Au pairs are often foreign.

BEN: Oh, okay.

DANIEL: Yeah. The term AU PAIR means “on a par” or on equal terms. It used to be that before World War II, servants would look after the children in upper class homes, but after the war, that sort of structure broke down and people were less likely to be in the servant group. So, au pairs filled that void. They were often upper class girls who wanted to find work in a family and be considered on a par with family members. They would eat with the family, they would go on holidays together.

BEN: Oh, okay. So like, it’s a nanny who isn’t working class.

HEDVIG: That’s the probably the origins. The way it is now, I think it’s more… it’s that kind of work role, but you might still not be a rich person.

BEN: Right.

DANIEL: So I want to throw my weight behind this term: AU PAIR STATE. I feel like it may be a term of the year.

BEN: I like it. Do we have another?

DANIEL: Last one. You know how we’ve been talking about big data?

BEN: Yarp.

DANIEL: Well, here’s one from Paul Musgrave @ProfMusgrave. You know the tired-wired-inspired meme?

BEN: No.

DANIEL: Oh. Something that’s bad, something that’s good, but something that’s awesome. So “tired” is: big data. “Wired” is: massive data. But you know what’s inspired?

BEN: What?

DANIEL: Small-batch artisanal data.

[LAUGHTER]

BEN: Oh, god.

HEDVIG: Ooooo.

BEN: Is this a real thing, or are they just pisstaking breweries?

DANIEL: He’s just taking the piss, but I’ll tell you what: Next time I do a small project full of hand-cultivated data, I’m going to call that my small-batch artisanal data.

BEN: I love it.

DANIEL: Craft data, if you will.

BEN: What a great way to… to just like… Like, if you were a nutritional scientist, and you just — like a lot of nutritional studies do — just have, like, a sample size in, like, the less than tens. And you’re just like: No, it’s not, it’s not a bad sample size. It’s [aɹˈtɪsənəl].

DANIEL: That’s right. I said [aɹtəsˈænəl], didn’t I. Art is anal.

BEN: You did.

HEDVIG: Yeah, you did. That was amazing! Please do it more often.

DANIEL: [aɹˈtɪsənəl]. That’s it.

BEN: There you go. Good job.

DANIEL: I’m gonna use it next time that my experiment doesn’t work. And then I try it again on the subset of the data!

BEN: Yeah! Yeah, yeah.

DANIEL: I’m not p-hacking. I’m…

BEN: P-hacking, now known as artisanal data mining.

DANIEL: It’s artisanal!

DANIEL: So: MEN-CHILDREN, AU PAIR STATE, and [aɹˈtɪsənəl], [aɹtəsˈænəl] [deɪtə]. Or [dætə].

HEDVIG: Art is anal. Data.

DANIEL: Art is [eɪnəl dæteɪ].

BEN: Oh my god, you two. Stop. [LAUGHTER] And this is Ben Ainslie reining you two in. Now we know things have gone deeply awry.

DANIEL: What’s happened to us.

[DANIEL and HEDVIG have the giggles]

BEN: Well, if you’ve got any questions for Daniel, then do feel free to give him a ring at 9260-9210. Or you can drop him an email in the studio, talkthetalk@rtrfm.com.au.

HEDVIG: We are also on all the social medias everywhere. That is Twitter, Instagram, Facebook. I’m going to convince the rest of the group to set up a Myspace as well.

BEN: Stop it. No. Stop.

DANIEL: Oh my god. We’re even on Mastodon as well, can I just say?

BEN: What is Mastodon?

DANIEL: Yeah.

BEN: You know what? I don’t even want to know. You guys? I’m done. I’m done with this show. Let’s finish.

[MUSIC BREAK]

DANIEL: That was the Au Pairs with “Diet”. Classic rockers from the ’80s. I never noticed how much they sounded like the Smiths before, and I think that actually predates the Smiths. This is Daniel on RTRFM 92.1. You’re listening to the closing minutes of Talk the Talk.

Zeno says: Hello, Talk the Talk. In Italian, nephew and grandson are the same words. That’s interesting.

Cath says: Hi guys. Loved the show. Just had to say I had to Google SHITPOST. Just saying.

Also Zeno says: I’m a regular listener, but I don’t know what shitposting is. Please explain. Well, okay. Shitposting is just posting stuff that isn’t very good or that might be offensive. It was… I tried to get it as a candidate for Word of the Year in the American Dialect Society last year. Didn’t work. We’ll see if I can try again this year.

Andrew phoned up, said: You know, ANUS is Latin for grandmother, but it’s also got a connection to RING like ANNUAL and ANNULAR. Is there a connection there? I had a look in Etymonline? No, doesn’t appear to be a connection, but I really appreciate the thought. Thanks, Andrew.

Carissa says: Daniel, whenever we have a family get together with the extended cousins, we always get into a debate about first cousin, second cousin, cousins once removed and so forth. No one can ever get to the bottom of the correct term for the relationship between my daughter and my cousin’s granddaughter. Yawn. Bores me to tears, and I just prefer cousin for anyone not a sibling. What about you? Well, let’s see: your daughter and your cousin’s granddaughter. So if we start with cousin, and then we go one level down on the pyramid for your daughter, two levels down for the granddaughter, then they are second cousins once removed. Hey, if you want a copy of that relationship chart, it’s on our blog, talkthetalkpodcast.com. Also, says Carissa, COUSIN is a pretty funny word all on its own. Don’t you think? I do. I think it’s especially funny because it’s one of those rare gender neutral kinship terms in English. But not in French, interestingly. Comes from CON SOBRINUS, your mother’s sister’s child. The CON is the WITH.

Leonard says, I am a 9-year-old boy named Leonard, and I have one question for you. Why do two words have the same spelling, but they both have totally different meanings, like MEAN and MEAN or ORGAN and ORGAN? Great question, Leonard. It’s like this: sometimes it’s because there are two things that we think are kind of similar, so it’s just easier to use the same word again, instead of creating a whole new word. So ORGAN is like that. It comes from Greek ORGANON, and it meant “that with which one works”. The working thing is important because there was probably a word in Proto-Indo-European *werg, and that’s where we got WORK from. But *werg is also the ORG- part of ORGAN. And it just met a tool for doing stuff, but it also meant a musical instrument. They were calling musical instruments ORGANS in the 1100s — any musical instrument, not just the kind that looks like a piano. But then by the 1300s, they stopped doing that, and they only used the word for what we call an organ, and then the organs for the body came around about the same time because it works. So there you go.

That’s one reason why words can look the same, but it’s also because sometimes there are words that start out different and then they converge. So the word MEAN for “intend” — that’s what I mean — comes from Old English MÆNAN, to intend. Simple enough. But the word MEAN — meaning “cruel” — came a different way. It came from Old English GEMÆNE, which meant something that everybody has. And then it meant “not very good” and then it meant “cruel”. So at first this word sounded different. We said GEMÆNE, but then all over English, people stopped saying the GE- part. So it just sounded the same as MENE. And then the word, the MEAN, like the average… that was from Latin MEDIANUS and the D dropped out. So that sounded the same too: MEIANUS. I mean, nobody meant for these things to happen, but it didn’t matter because it didn’t make the words harder to understand; it worked well enough. So that’s why words sometimes sound the same. If you want to know more about the meanings of words, you should check out the Online Etymology Dictionary and that’s etymonline.com. We support them on Patreon, and we think that you should too.

Oh, but he says: This is not part of my question. Me and my family play Talk the Talk Against Humanity, and my favorite one is: Nobody puts Daniel’s accent in the corner. Thanks for the question, Leonard. You can play Talk the Talk Against Humanity, that’s up on our Patreon page along with lots of other goodies. In fact, we’re due for an update, so watch out for that.

Thanks to Jerry, Nicky, Termy, Ann, Helen, Jack, Matt, and Sabrina. Keep listening to Darcy, who’s going to be taking us Out to Lunch. Thank you for listening and until next time, keep talking.

[END BIT]

BEN: This has been an RTRFM podcast. RTRFM is an independent community radio station that relies on listeners for financial support. You can subscribe online at rtrfm.com.au/subscribe.

KYLIE: Our theme song is by Ah Trees, and you can check out their music on ahtrees.com, and everywhere good music is sold.

DANIEL: We’re on Twitter @talkrtr. Send us an email, talkthetalk@rtrfm.com.au. And if you’d like to get lots of extra linguistic goodies, then like us on Facebook or check out our Patreon page. You can always find out whatever we’re up to by heading to talkthetalkpodcast.com.

[Transcript provided by SpeechDocs Podcast Transcription]