Indigenous languages matter. They’re part of Australia’s cultural heritage, and they’re a way for Aboriginal people to communicate, and connect.

This includes Indigenous signed languages. In the push to recognise minority languages, Indigenous signed languages deserve some attention of their own.

Signed language researcher Rodney Adams of the University of Newcastle is telling us all about these languages on this episode of Talk the Talk. Our Auslan interpreter was Sarah Dearlove.

Listen to this episode

You can listen to all the episodes of Talk the Talk by pasting this URL into your podlistener.

http://danielmidgley.com/talkthetalk/talk_classic.xmlPromo

Heyyy, it’s Jeff in the studio! It’s always a hoot when Daniel and Jeff get together, and this time Jeff has a few questions.

There’s a lesson for this one. No matter what it is that you dislike in language, there’s someone with the opposite preference or experience.

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/30204253

Video

Also at https://youtu.be/nUATqAKwazE

Full interview

Daniel got the chance to catch up with comedian Steph Tisdell when she was in Perth recently. She laid a Word of the Week on him, and talked about her language background. As an Aboriginal woman, Steph is uniquely suited to talk about the intersection of race, comedy, and language. She’s also hilarious.

Thanks to Steph for a fun chat! Check her out at stephtisdell.com.

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/interview-with-30148899

Leave That In!

How should wars be fought? With drinks! At least that’s how Denmark and Canada do it.

Hedvig shares a pro tip that’s too much even for Ben. Finding Ben’s limit? That’s something.

Not everyone is happy with Merriam-Webster’s non-binary they. They’re sticking with Oxford, which never updates.

Why was ginger used for people with red hair?

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/30281656

Reflections on 379: Indigenous Signed Languages

Welcome to Reflections. 🎹

What a huge episode! There were a lot of elements that had to come together.

- The interview with Rodney Adams. Hedvig deserves all the credit for setting this up, but the crew at The University of Newcastle made it all possible by recording the video. We really want to do more with signed languages, but it’s challenging in a podcast medium. I’m really glad I learned Final Cut, though — that made it possible for me to take all the audio and video and put it into its final form. Our next signed language project is going to be about poetry in signed languages. At least, that’s the plan. A few listeners have asked us about it, so watch for that.

- The interview with Steph Tisdell. It was so great to meet up with Steph, and if you’ve listened to the full interview, you can tell she’s a hoot to talk to. Edited out: about six minutes where the fire alarm went off. We didn’t care — we kept talking, and so I suppose we deserve to burn in a hotel room. Life well spent.

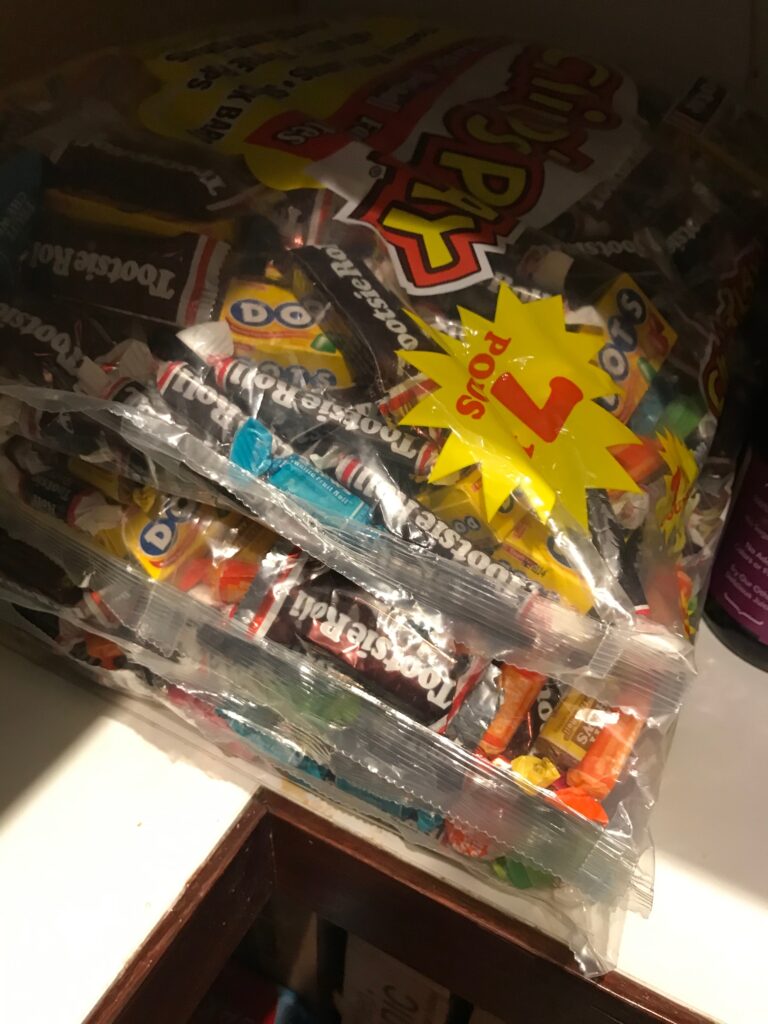

- The snacking. Oh, the snacking. You can hear Ben reacting to Hedvig’s stash, but he didn’t see mine! But you can. Two photos are Hedvig’s Swedish marshmallows — which I really really want to try — and chocolate. Photo 2 is my stash. I think you can see three different kinds of chips in there, plus some Kraft caramels that I brought back from the States. Photo 3 is the biggest haul. It’s something like 28 pounds of Tootsie Rolls, Dots, and associated treats. No, I’m not going to eat them myself. They’re for Hallowe’en. Before you even ask: Yes, we do get that many children trick or treating; and no, I’m not building a candy house to attract them. They come on their own.

I liked the first part about Old Gold chocolate; Australians will know what I mean.

So I have an editing question. The first part was longish, and I was aware that it was time to get to the news, but I just enjoyed that bit so much that I didn’t mind letting it run. In times past, I might have consigned that part to the Cutting Room Floor, but it all seemed relevant, even the etymology of doozy. And I have this idea that the enjoyment of the conversation is as important as the information. What do you think? Tighten it up, or let it run as long as it’s entertaining?

Thanks for reading. This has been… Reflections. 🎹

Also at https://www.patreon.com/posts/30255108

Patreon supporters

We’re very grateful for the support from our burgeoning community of patrons, including

- GreenlandTrees.org

- Adie

- Carolin

- Chris

- dcctor woh

- Lyssa

- Termy

- Andy

- Binh

- Bob

- Damien

- Dustin

- Elías

- Helen

- Jack

- Kitty

- Kristofer

- Larry

- Lord Mortis

- Matt

- Michael

- Sabrina

- Whitney

You’re helping us to keep the talk happening!

We’re Because Language now, and you can become a Patreon supporter!

Depending on your level, you can get bonus episodes, mailouts, shoutouts, come to live episodes, and of course have membership in our Discord community.

Show notes

Indigenous language puzzle receives missing piece after freak find buried in old book – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-16/indigenous-language-puzzle-receives-missing-piece/11516334

Ngunawal language revival project | Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

https://aiatsis.gov.au/research/research-themes/ngunawal-language-revival-project

Having an elder brother is associated with slower language development

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2019-09-elder-brother-slower-language.html

NWDP – 2019 – Deaf Australia

https://deafaustralia.org.au/nwdp/

Meet Rodney Adams, a Koori deaf researcher taking in Summer School – Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language

https://www.dynamicsoflanguage.edu.au/news-and-media/latest-headlines/article/?id=meet-rodney-adams-a-koori-deaf-researcher-taking-in-summer-school

Mr Rodney Adams / Staff Profile / The University of Newcastle, Australia

https://www.newcastle.edu.au/profile/rodney-adams

Merriam-Webster adds non-binary prounoun ‘they’ to dictionary – The Washington Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2019/09/17/merriam-webster-adds-non-binary-prounoun-they-dictionary/

https://twitter.com/BCDreyer/status/1174785492359008258

Steph Tisdell’s website

https://www.stephtisdell.com

ABC Indigenous on Facebook | Boomerangas

https://www.facebook.com/pg/ABCIndigenous/photos/?tab=album&album_id=2191371370957268

Rough transcript

Rodney Adams interview

[MUSIC] We are here with Rodney Adams, who studies Aboriginal signed languages. And our interpreter is Sarah Dearlove. Hello, Rodney and hello, Sarah.

Hi, good day, how are you? Lovely to be here this morning. I’m looking forward to this little chat. Be able to share some stories about indigenous signed languages.

Excellent, when we think of signed languages in Australia, we usually think of Auslan, [BLANK_AUDIO] Which has its roots in English. And many people are surprised to find that there are Aboriginal signed languages. Where do they come from? What’s their history? [BLANK_AUDIO]

Well, really Auslan arrived in Australia roughly 200 years ago, early 1800s. So its origins are in BSL, which is British Sign Language. So with so much British history, deaf communities moved from Britain to Australia. And more and more people moved to Australia. And the language change developed and grew. Auslan is an incredibly young language in that instance. It’s been sort of established around the same time as colonial settlement. Now what we do know is, and there’s been quite a bit of research by myself and other colleagues of mine, that have actually found that Australian indigenous languages have existed for such a very long time, for thousands and thousands of years. Now, just as we have indigenous spoken languages for everyone, there is an indigenous signed language. So there’s some research being undertaken that’s really starting to explore these ideas of finding them, these small clusters of Aboriginal people that are still continuing to use these languages. We’re also looking at dialect differences that will exist. So not only language differences, but dialect differences. So it’s a huge area of study. And what we’re actually finding is that the young new signed language, which we’re now hoping to be able to publish a book very, very soon in that area, shows that indigenous signed languages have been around for such a long time and they’re certainly much older than Auslan. [BLANK_AUDIO]

How many indigenous signed languages are we talking about here?

Oh, that’s a huge question. And first, we need to determine the number of indigenous spoken languages for certain. And what we know is that the research shows different numbers. Some sort of estimate 250. Some estimate it’s well over 400. So I would expect that signed languages would sort of have been thousands of them once upon a time. But how many are still existing today, we’re yet to determine. Again, I’ve been in contact with a number of different people. I presented a paper recently at another indigenous signed languages conference. And from that, I’ve established a lot of contacts. So there’s certainly some information out there. What we need to do is sort of collate it, collaborate, and then work together for the revitalizations, which is gonna be really exciting to see.

I wanted to ask, I’ve heard and I don’t know much about it. But I know that there are some places in Australia where gestures or signs are used by hearing people. And that that might also interact with the development of signed languages for deaf people in those places. I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit more about that.

Yes, certainly, so there are some areas, again, some areas of research. What you’re referring to was called hand talk. And people assume that when we’re speaking of hand talk that it is just gestures, but it is essentially the foundations of signed language. So yes, they’re gestures, but when we add to that the phonology and the syntax of languages and they have the characteristics that make any language a language, then what we actually have is something that becomes signed language. It becomes meaningful. The brain detects patterns of language, and it allows the brain to actually develop it. Gestures, on the other hand, can be used in isolation, or they can be used in combination with signed language vocab. Then we can add grammatical structure. And then that’s what we actually say is language development. There are parts of the East Coast of Australia. And there are certain little pockets where we’re seeing the use of signed language reemerging. A colleague of mine who’s in Canberra, her name is Lauren Reed. And she’s done some research into looking at signed languages and assumptions that some of these languages have effectively died out or disappeared, but they are still being used. What we need to do is meet these communities and film them before people pass away and take language with them. [BLANK_AUDIO]

It sounds like indigenous signed languages are having some of the same issues that indigenous spoken languages are. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Yes, yes, and it’s a case in point. So at the moment, what we actually do is trying to get some funding grants, which will allow us opportunities to video and record in other ways the use of language to engage with indigenous communities, allow a rapport to be built, which will develop trust, and then allow filming to occur. There certainly are some issues that affect indigenous signed languages that are common with those of indigenous spoken languages. And it’s about collating as much information as you can. And I’d love to see the use of indigenous signed languages by indigenous deaf populations in Australia. Recently, in the deaf young new community, there was a filmmaker who won an award and who is a young new signed language user themselves. But looking at the importance, the significance of sort of preserving these languages, developing relationships. He spoke about the importance of developing relationships, particularly when you’re sort of working with isolated communities. I’m thinking of an example in Port Hedland in WA. I’ve recently had someone get in touch with me. And they’re looking at sort of researching, recording and sort of keeping for longevity these languages. There’s certainly a lot going on. I’m also aware of some stuff going on in [UNKNOWN] which is down sort of in WA again. And then we’ve got [UNKNOWN] language. Look, there are plenty of them out there. But because the focus has been so much upon the use of indigenous spoken languages, it means that signed languages have been forgotten or pushed to the side, which is why I want to ensure that we’ve sort of got that nice balance between the use of all of the languages. Because this is the year of indigenous language, and that has to include the use of indigenous signed languages as well. [BLANK_AUDIO]

I was wondering, I did my undergrad in linguistics at a department that was shared between spoken linguistics and sign linguistics in Stockholm. And it meant that we got to learn some basic Swedish sign, which is great fun. And I learned that there can be some differences in how signed language is used if they use a lot of signs with two hands, or if they use a lot of signs with one hand. So Swedish sign and American sign differ bit in that. And I was wondering if you could tell us a little bit about differences between different indigenous Australian signs in their sign characteristics. [BLANK_AUDIO]

I think probably one of the more important points is to clarify that when we’re talking about indigenous signed languages They’re natural, and by that I mean that they’re not reliant upon spoken language influence. So in for example, in Auslan, there is a lot of finger spelling that exists, but that’s where we’re using English terminology. And in Australia we use two hands to create the alphabet. However, in the past indigenous sign languages, they would have signs that were relevant or different words for different use of language. But there was no finger spelling method. So indigenous sign languages would be more visual representations of the world around us, as opposed to a spoken language or an alphabetical formula that exists in other spoken languages. So in the instance of American Sign Language, British Sign Language, French sign language and here in Australia with Auslan, we see huge influence of the spoken language, the dominant language in a country, influencing the signed languages. But again, like any language, whether it be spoken or signed, there’s diversity of users, and there’s also diversity of dialect. And where we have a spoken language, we’ll always have a signed language. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Do you think that you could show us some differences between different indigenous signed languages and maybe even between Auslan and those languages.

I might be a wee bit rude because these are only a couple of rude ones that I actually remember so I’m unsure how to proceed. Okay, so.

We like the rude ones, we’re all about the rude ones. [LAUGH]

[LAUGH]

Okay, so now I know for example in Plain Indian sign language, northern United States, the North Americas some of their stuff is just absolutely incredible. So they’ve done some really great research there. And they made a comparison between ASL which is American Sign Language and Plain Indian sign language for a number of different words. One sign that they use in Plain Indian sign language for father is this, this is father.

Oh.

Okay, are you with me? Now.

Yeah.

They use this as son, as in the father’s son, yes. Got it.

You’re with me? Yeah. So there are other examples, certainly here in Australia a young woman is referred to like this and an older woman is referred to like this. So signs like that certainly make sense. They’re certainly easy to remember because they’re so very obvious. As opposed to some of the European sign languages and Auslan is one of those. ASL, American Sign Language, being another, because they’ve essentially been borrowed from European sign languages. So in Europe different sign languages exist, but they’re certainly more arbitrary. The individual vocab is arbitrary. There’s no direct correlation between what you’re seeing and the symbol it’s being used to represent or the word in this instance. But when we find some research that shows that indigenous sign languages and the intelligence and the richness of language, it makes incredible sense. They’re incredibly iconic, which makes them easy to remember. So just like those examples I showed you just now, I think it’s brilliant. That’s really cool.

And yet we notice that a lot of people have this misconception that signed languages are just iconic. If you want to say a thing, that sign will look like the thing. And that’s not always true, but it sounds like it’s true a lot. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Well, it’s a natural reflection of the use of signed language. So when we sign, we’re trying to sort of make reference to something visual that we see and we’re experiencing in the world. Some of the kinship signs, in relation to indigenous families and family history, are very different, when they compared to Europe centric signed languages, like Auslan. So, an example that I particularly love here, is an Aboriginal sign language referring to family like this. So the hand is placed on the spine, and that is reference to grandmother. That sign is so different, because what we have as sign language users is a signing space. And in European centric sign languages, that’s in front of us.

Indigenous signed languages allow us to refer to the back of us. So grandmother on the spine, because grandmother is backbone of community. So that’s incredibly significant. And it’s an incredibly significant sign that genuinely reflects cultural reference to grandmother. So yeah, I think it’s beautiful. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Another cool thing that, I have some friends who do more sign language. And there are some great benefits to signing that you can’t do when you speak. For example, when you speak, you can’t say two things at the same time. But when you sign a narrative, you can possibly have two agents or a narrative you could have more things going on at once simultaneously. In a way that unless you have some sort of polyphonic ability to do two tones at the same time with your mouth you can. And I was wondering if that was a practice that people use also in Australia sign that sort of I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about like the, how do you say, the differences between sign and spoken that open up more opportunities like this like the sign space?

Probably the major difference that exists between spoken and sign languages is. Okay, so as far as sign languages goes, they’re certainly more flexible. And what we can incorporate into one sign can convey an entire sentence of meaning in the English language. So, like indigenous spoken languages, they’ll often have one word that can convey an entire concept. So, in reference to some of those differences, okay. So, certainly there are grammatically differences that exist between spoken and sign languages. So, for Auslan itself, we’re certainly much more flexible in word order. We can play around with it a little bit more. We can maintain meaning, we use what are referred to as the non manual features of Auslan which is essentially the facial expression. So those facial expressions, those non manual features, are essentially a reflection of the intonation that speakers use when they play around with their voice. So we use facial expression to convey tone, which can also add so much more meaning to words themselves. When you are a sign language user, you can certainly be incredibly subtle with your facial expressions. And again, you can change the meaning that hearing people in the room may not catch, but some deaf people often don’t understand some of those intonations that exist. Sometimes you can use your voice to sort of reflect a slight bit of sarcasm. And we as deaf people, that’s lost to us. However, we can use those same things with a slight adjustment of the eyebrows to suggest that we’re being incredibly sarcastic and other hearing people in the room won’t know what we’re talking about.

[LAUGH]

Exactly, exactly.

I am just wondering about what would be an example of a sign that conveys multiple concepts, in a way that maybe spoken English or even Auslan don’t?

[SOUND] We’re asking you for a lot of complicated things. [LAUGH] So this is the sign for none of your business.

[LAUGH]

I’m really clueless.

None of your business. [LAUGH]

Okay.

That’s a good sign to know. None of your business.

Is there, do you have a sense of how that signs, what I’m saying is, my hand is in two fingered shape. I’m pointing to my nose. And then I’m turning my hand around, and using that same shape directed towards somebody else. Is that because, I feel this is just a guess, as to how this symbol got to be that way, is it because that person wants me to not stick my nose in their business? Is that what’s going on there? [BLANK_AUDIO]

Oh, that would be really difficult to say for sure, because a lot of signs are essentially as I said before arbitrary, there’s not necessarily a direct correlation between what you see and what’s actually, and what it means. I don’t know the precise history of that science. I couldn’t say with any certainty, but it’s certainly some of the wonderful things about researching languages, generally, and asking why people use the vocabulary that they do. There are some signs that you sort of look at and think, gosh, who knows where that came from, or why it came to that particular sign.

[LAUGH]

But, yeah, it’s a really question to answer, I wouldn’t like to answer it with any real certainty.

Well, now, really, I understand that, but now I’m really curious. When we are looking for the etymology of words, the word histories of spoken English, we can look in books from long ago, and see where the first instance of a word came from. And we can make some guesses about how words, in spoken English, got to be that way or in written English. [BLANK_AUDIO] If you wanna find out the etymology, the word history for a sign. Where do you go? [BLANK_AUDIO]

[INAUDIBLE]

[COUGH] [LAUGH]

It’s actually a really valuable question though, because, very recently, deaf person from the United States was doing some research and looking at this world of science and new terminology that exists, but there are no signs for these new terminology. So, whether it be the world of science or technology, this individual researchers sort of looked at and met with a number of deaf people, and what they actually did is, created an new vocab list of around 1000 signs that allowed them to sort of match new tunes that exist in the English language that make reference to science and technology. So it’s certainly a field of academic study, that allows vocabularies of all languages to change and develop over time. But it’s sort of requires the use of, rather than having an interpreter finger spell an English word every single time it comes up. Just like spoken language, the dynamics of language, whether they be spoken or signed are always evolving and changing. They have to to keep up with the times. And that’s actually a really significant point, because some indigenous sign languages we do know have been lost. However, if we can engage with the meaning of language within Aboriginal cultures, as signs that can be conventionalized, then we can go on to use them and preserve them, and redevelop the use of some indigenous languages again. Already on top of what we already know exists. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Is there [UNKNOWN] so I know that there are many different sign languages in Australia, and maybe as many as [INAUDIBLE] same question as how many spoken there are. Is there naturally or intentionally, are there any sort of signs of people amalgamating to sort of join different sign languages? Is that a process that’s happening or is that not the case?

Amalgamating with wash.

With each other, I’m sort of merging, making sort of contact sign languages that are shared across groups that used to have distinct languages. [BLANK_AUDIO]

Essentially, the answer would be, it makes sense to try to avoid that. Because what we then do is sort of recolonize language. So what would happen in that regard is, the weaker language would be taken over by the dominant language. So, we know that that’s what happened here in Australia, Ozland, arrived and indigenous sign languages died out, the same things happening in Samoa, in Fiji. It’s happening worldwide. And in those instances where we’ve got interpreters that travel to different parts of the world and work with children in developing countries, they bring their language with them. But what’s important is the preservation of the home language. To encourage it to remain a dominant language. Because it fits appropriately with their culture, rather than borrowing too much in amalgamating. We do know that happened to you in Australia when you’re seeing a lot of signs that are very American. And an American sign language has become, rather a dominant sign language worldwide. Which is something that we’d rather not see that happen. Because it’s about preservation of a number of different languages that exist in different parts of the world. So, and it’s about sort of conventionalized signs locally, that fit with the context of where you are, in this instance, Australia.

I wanna ask a little bit about indigenous signs and how they get new words. Because this is a challenge for indigenous spoken languages. Maybe they don’t have a word for things, for scientific terms, is there a process of lexical creation for these languages?

Well, I think one of the sort of more important areas here, so a colleague of mine, who’s name is Jackie Troy, who’s working with other indigenous communities, to try and to establish June naming of places. So, particularly here in New South Wales. So, in New South Wales, we’ve got the Indigenous Languages Act, which means that we’ve got government supporting this particular area. So it’s about not being rid of the English word, but adding the indigenous word that existed before, to make reference to this place. So we’re seeing some examples. So for example, in Sydney. The word Sydney, the sign is this, because it makes reference to the Harbour Bridge. The Harbour Bridge itself is only very new, therefore the sign is very new. So what 1937, Sydney Harbour Bridge was launched, so the sign itself, is less than a hundred years old. However, if we go back to the indigenous word for that place, which is gadigal, and then we can actually make a visual representation of gadigal, that’s what we need to actually find and discover. So gadigal comes from the word getty, which is the people of the grass tree. The new word for that place is Sydney. But in a visual representation of people of the grass, tree, would be a visual representation of the grass tree. So it’s not about getting rid of the word Sydney or the sign Sydney. It’s about acknowledging and respecting languages that came before, and I think we’re gonna see more and more of that. And I think we’re gonna see more sign languages making a better reflection of how the world looked, pre- colonization, pre the harbor breach, more like the gadigal tree. I beg your pardon, the people of the grass tree, the gadigal people. So, yeah, that’s what I think it’s about. [BLANK_AUDIO] I like that.

I’m [UNKNOWN] did you have one? I have another one. Oh, no, you go ahead.

One of the encouraging trends for Indigenous spoken languages in Australia is, that people are returning to their traditional languages. Is this happening with indigenous sign languages? [BLANK_AUDIO]

Oh, yes. But, it’s really only just begun. We’re only sort of at the surface level of it all. Very recently, I presented a paper at the PULiiMA conference, which was in Darwin, an indigenous language conference. And we spoke about indigenous sign languages there. There were a number of people that came up to me afterwards who said, I never thought about indigenous sign languages. And it’s something that we really do need to be mindful of and respectful of, because it’s very much a part of indigenous communities. It was very much about our social and emotional well being. It’s about empowering individuals to sort of develop, and re-develop confidence, pride in self, just like deaf and hard of hearing indigenous people need those same things, that sense of self, that sense of identity through language. So yes, but it’s only a very new field of area, it’s something that people are only just becoming aware of. And it’s about sort of engaging with indigenous deaf and hard of hearing people, in the same way that spoken languages for indigenous people as sort of helped them to become more confident and get in there, and sort of revitalize. We’re only at that. I think I may have gone off to us with that question. I don’t know if I answered your question. [BLANK_AUDIO]

I think so.

I think so. [LAUGH] Sorry. May I just add one more thing? Sorry, if it’s okay? Yeah.

So, the New South Wales Indigenous Languages Act of 2017 hurrah, I think as you know, most of Australia is now looking to New South Wales to see what happens in regards to this. I’ve had a few people saying to me, please, do some research into indigenous sign languages of New South Wales, because it’s going to help future projects. It’s about deaf and hearing community sort of being able to explore their own past. The way ancestors communicated, because not all indigenous communication was verbal. There was a lot of hand talking gesturing that was natural for indigenous communities, and they use these systems in Canada only a few months ago. They’ve approved two different bills there. In relation to indigenous sign language. One was, forgive me, the Indigenous Canadians Languages Act, and within it, they’ve actually stated that they will allow some exploration and research in to Canadian sign language or North American. So that would include the use of plain Indian sign languages. And other modes of communication that existed. The other bill they’ve enacted was the Canadian Accessibility Act. So obviously, in regards to deaf and hard of hearing people, they’ll fit into this category as well, so it allows another opportunity for people to access information. To not just English, but to indigenous language. Because English has always been the primary language, for such a long time, has been the primary. So it’s great for us, as Australians to be able to see what’s going on overseas and see similar things going on here in New South Wales. But there is one little story from a, now, the battle of Little Big home.

I’ve seen this video. Ah, okay, so.

There’s a-

In the USA and Canada. Having lost the battle of Little Bighorn, it was quite a defeat, and most people are familiar with the story, the general cluster having died at that particular battle. But, five years after the event, someone was writing, documenting it. And what they actually witnessed was, this two day battle, then the nomination of a chief, a local chief, and his name was Red Horse, Chief Red Horse. So Chief Red Horse was part of this retelling. And he was asked to tell about the battle, the two day battle. There were two things that popped up after he told his story. He told his story in indigenous sign language. The second thing is, is that he wasn’t deaf. He was a hearing man. So, why he chose to tell this story in sign language, such a significant story about the defeat, and why he chose to tell that story in indigenous sign language. Well, we still don’t really know the answer to that question. What we do know is, that if he was a hearing man, and he was able to use sign language, then sign language wasn’t a language that was used only by deaf people. So that shows just how significant it is. Plain Indian sign languages is now being taught in North America and Canadian schools, do by hearing enter deaf students. Because they recognizing the significance of the language as it existed in the past, and they sort of using it as a way of overcoming issues that currently exist, particularly in relation to social and emotional well being. Sort of, empowering young people through the use of different language. That story had a huge impact on me when, I found that out, and American Indian chief hearing, retelling a story about a huge battle in sign language that’s incredibly significant. Really significant. The event itself is significant, but the language he chose to retail it. But so many of us don’t know it, because so many people think that sign language is just for deaf people. But it is, in fact, a language that can be accessible for all of us, and I’ve got a colleague of mine, who said, to sign is human. Because, hearing and deaf people once upon a long ago, used signs and gestures have a way of communication. Communication wasn’t limited to speech and listening. And it was a way that entire communities could get together, despite different languages. They could overcome barriers that exists with spoken languages. It was all overcome for different tribes.

That’s a really good story, and it’s what I’ve been told as well. I did some classes actually in Canada, and we had a sign language, a deaf Canadian come and talk to us about indigenous sign languages. And I think you’re right. Canada is very interesting to look at. A place to look at this, because they already have a lot of legislation regarding the use of French and English. So they’re already sort of a little bit aware of the the need for certain support for different languages. And they’ve also brought that to the sign languages. And I saw a video on YouTube that I’ve been trying to track down again, which was the story we telling us as a big big horn. American sign and Plains Indian sign. I’ll see if I can get it for our listeners, cuz it’s a simultaneous, they both signing at the same time. So you can see the story.

Oh, wow!

And it’s a great way of showing the differences. But, that’s something I was wondering, if you could also talk a little bit about if you wanted to, about Indigenous Australian signs. About the use of hearing people using it, as a way of overcoming boundaries with group boundaries and coming together, and being able to share stories and narratives. And have meetings in an easier way, because the hearing people share signs rather than using spoken languages.

[COUGH] [BLANK_AUDIO] We certainly know once upon a time, when indigenous people met from different tribes, they would use gestures as a way of overcoming the limitations that exist for spoken languages. But it just sorta makes me think of another story. Bungaree, a gentleman who travelled with Matthew Flinders and helped him to navigate Australia, circumnavigate Australia. Bungaree was essentially responsible for each time the ship, particularly on the East Coast for example, any time they needed to port for, if they’d run out of food, or water, or other supplies, or needed repairs to the ship. Bungaree was essentially responsible for communicating with the local tribe that met them in the area. So there were times where he was using communication types, gestures and hand talk to overcome the boundaries that existed between spoken language, so things like we’re looking for food or water, or sort of clarifying directions and things like that. If they needed new wood because the ship needed some repairs, he was able to use a range of different communication systems that overcame the limitations of just using speech. So if you can imagine that, traveling around the entire coast of Australia using that mode of communication to communicate with everyone. I think what’s sad is that those communication systems have been lost to us as a society. Because it’s something that indigenous communities have used for such a long time. And I think it’s important that we acknowledge that and bring it back, to sort of preserve language. It’s something that people knew well, once upon a long ago. And so much if it’s been lost or is in dangerment of being lost. And there’s so many different reasons to consider it valuable, obviously.

I sometimes-

Go ahead.

As a hearing person sometimes, I go to Germany sometimes and people don’t speak English. And I speak a little German. And I try to communicate with other hearing people with some gestures that I think would be shared across European. It’s like I’m trying, but a lot of people aren’t used to interpreting it. So it’s such an obvious, effective, good way of overcoming boundaries. But most people aren’t used to it, so it usually doesn’t succeed. But it’s something that hearing to hearing people still can benefit from.

Yeah.

For sure.

This is making me-

Sorry, I’ve got another story that comes to mind. Would you like another story? Yes, please.

So yeah, I do love a yarn. Okay, so my partner was once in Germany, and she was with a group of Australians. They went to Germany, they were in a cafe. And they were all sorta sitting at this table having a look at the menu, which was obviously printed in German. Not one of them understood it. So the waitress came around to the table, trying to determine what they wanted to order. There was one person who said they would like a cup of tea with just a little bit of milk. But the German waitress spoke no English, and the Australians had no German. So the communication was going nowhere quickly. Everyone was getting frustrated and a little bit narky. You could see the German woman was getting incredibly frustrated trying to convey, I want some milk. So my partner who’s deaf was sorta looking at this conversation, waved for the attention of the German waitress, looked her up and down cuz she was rather voluptuous, shall we say? And she did this. She just did this.

[LAUGH]

The German waitress got it straight away though. She nicked off to the back of the kitchen and she came back with a jug, a jug no less, of milk.

[LAUGH]

But I think that absolutely shows how visual communications can overcome those barriers that exist for spoken languages. Perfect example, I reckon.

I think we need to say for people who might be listening to this, that Vernie made a gesture. Daniel, do you wanna try?

The pulling of the teat.

[LAUGH]

Very iconic, very clear, I understand why she got it.

Yes, exactly.

At which point, the waitress had to determine the level of specificity required as to what kind of milk was being requested.

Yes, cow milk and not human milk. Yes.

[LAUGH]

Well, she came with a jug, so.

[LAUGH]

It was probably a little bit more than they needed. [LAUGH]

Possibly. Sorry, I just wanna go back a second. Many indigenous Australian spoken languages are a little bit mutually intelligible. Can you tell me if the different indigenous sign languages are also kind of mutually intelligible, or maybe not? [BLANK_AUDIO]

I think with regards to sign languages, generally it’s easier to communicate because deaf people are naturally visual communicators. So we’re naturally doing this every day when we’re meeting with people here in Australia, when we’re meeting with people when we go overseas on a holiday. So obviously, the languages are incredibly different. But because we’re visual communicators, we can overcome the barriers that exist and we can make ourselves more easily understood. Whereas hearing people do tend to be very limited to the spoken language that they speak, and it makes things difficult to overcome. I would say generally speaking, that deaf people do incredibly well at that, whether it’s here locally or whether it’s traveling overseas. We’re used to making ourselves understood by people who don’t speak our language. So we are better able to overcome those language barriers that exist. Because we are naturally going to be able to gesture and make ourselves understood quite well.

And maybe more flexible and sorta tolerant of variations. I know a few, very few sign language and signs in Swedish, and I use them sometimes. But sometimes I use the wrong hand gesture or the wrong direction. But everyone is so nice and so, oh, she probably means this. It’s more flexible.

Yes, yes, yes. [LAUGH]

So you’ve been telling us a lot about indigenous sign languages. And we’re very grateful, but you have an audience. What would you like everyone to know about Australian, or about indigenous sign languages? [BLANK_AUDIO]

Okay, [BLANK_AUDIO] Really, I think, so working in the field of deaf education, I meet a lot of deaf Aboriginal people. And I think it’s the same for Aboriginal children. They wanna connect and reconnect with history, with their past, ancestry, past culture practices, traditional ways of communicating. That sort of helps them or empowers them. What we do know is that the benefits of learning language, and if we’re looking at indigenous populations, it’s about the social and emotional well being. So at the PULiiMA conference that I mentioned earlier in Darwin, everyone spoke about the benefits and how inspiring it can be for individuals to sorta find their own history, their own language. So whether that’s for a hearing person or a deaf, hard of hearing person, it’s essentially the same story. However, when it comes to deaf and hard of hearing people, languages have been doubly neglected. So I would like to see communities take up the same interest in the revitalization of sign languages, as they have for the revitalization of spoken languages. I think that’s probably the main thing I’d like people to take home. I’d like people all over Australia to just take more note, pay a bit more attention [BLANK_AUDIO]

How can people find out more if they would like to? [BLANK_AUDIO]

They can get in contact with me via email. I can send you out my email address very soon. But I think just sort of encouraging people to have a conversation about sign languages, about how valuable they are as communication systems. I think it’s focusing on, when we think about deaf and hard of hearing people, there’s such focus on speech and listening. So while these technologies and these methods can have all sorts of benefits, they’re not always successful and there will still be limitations. And if we’re looking again about indigenous communities, it’s about documenting and preserving language for longevity. What essentially we’d like to have is one day, a database that sort of has access to all of these indigenous sign languages where we can collate them from all over Australia. Because when we think about Australia and we think about sign language systems, it’s probably one of the oldest, they’ll be the oldest languages in the world. And they need to be preserved and we need to make sure that we’re reflecting these communities. I think we should be taking huge pride in knowing aboriginal and non-aboriginal can take such benefit from these ancient languages using gestures, and side languages as a mode of communication, and knowing that these have existed since Australia first began.

So we usually on the show have Indigenous Australian word of the week and we do that in our audio version of the podcast, and we’ll be preparing this also for sharing the video with people. So we’ve learned a few signs. We learnt none of your business, which I think was that Auslan or?

That’s an Auslan sign, yep.

And then one of the kangaroo science was this and then.

Yeah, kangaroo. There’s a few kangaroos, yep.

And then we had the various older women.

[LAUGH]

Yes, yes, the man, the woman. That was some of those were plain Indian sign languages as well, though.

Yeah, yes, I was wondering if there was one sign in particular that we could sort of share to our listeners and get them to maybe use or share with their friends that you think is a fun one just just one fun. One that we can sort of have them in little video snippet and get them to do, trying to think of something else.

Oh, okay.

I like all the kangaroo.

I know, that’s cool. [BLANK_AUDIO]

So this particular hand shape is internationally understood to mean I love you.

Yes.

So when we sort of look at the hand shape, what we’ve got is, it’s also used for emu. Not in the same way, but the same hand shape is used for emu. So sometimes, people will see that particular hand shape and think it means something. But in this instance, it means something very different again. So yeah, I think that’s just interesting that one hand shape can be used to represent either a concept of loving someone or an animal. Oh, you’ve put me on a spot. I want focus, I’m very specific.

That’s okay.

I’m sort of thinking about the kinship sign as well, I particularly like where the people remember grandmother. Yes, that’s grand mother.

Is that in Yonu sign or? [BLANK_AUDIO]

Yes, yes, other language groups do use that one as well. But again, there’ll be all sorts of variations all over Australia. But yeah, depending on culture and country and connection to land and all that sort of a thing. [BLANK_AUDIO]

All right, I think that’s great.

We have been having a chat with Rodney Adams, a researcher at the University of Newcastle. Sorry, am I getting that right?

Yes, that’s right.

Okay, so Rodney Adams, thanks so much for coming on and having a chat with us today.

Thank you. Oh, there you go. Dikugura is the local word for thank you. The gotta go language pronunciation. Thank you.

There we go. And thanks very much to you, Sarah Delux for being our interpreter today.

Pleasure. Thank you, Sarah. [BLANK_AUDIO] [MUSIC]